An Introduction to Contemporary Iranian Symphonic Music Performance Practice

The goal of this article is to define different aspects of Iranian symphonic music and provide a guide for performers to understand the related musical and cultural context and achieve a better interpretation. The term Iranian symphonic music often refers to the music written by Iranian composers using western instruments but incorporating elements of Iranian heritage.

I have spent the past 15 years working with three generations of Iranian composers. These collaborations have led to a body of works that has expanded the repertoire of flute music by Iranian composers. The majority of the examples in this article will be selected from this pool of technically diverse pieces to represent the topics discussed in each section.

During the past two decades, a new wave of composers emerged from Iran. This new generation is active in the global music community and has received international acclaim. With the emergence of any new musical language, there is a need for definitions, cultural context and consequently, practical implications of these contextual ideas. Currently, there is a lack of written material about this recent new wave of Iranian music. One of the principal reasons for this shortage is the confusion of definitions for the music coming out of Iran. It is hard to define what we call “Iranian music” and what genres/types of Iranian music we are dealing with. Having a unified definition for all these different genres/types will make it easier for a non-Iranian musician to find the related information. In addition, this accessibility will enable them to come up with a proper way of interpreting the music they aim to play.

Iranian music can be defined into three large categories:

Iranian Classical Music

Music using Iranian instruments and used mainly in Dastgah music and based on Iranian scales, modes and melodic ideas. Scholars refer to Iranian classical music as Dastgah (or Radif) music in many texts. Some Iranian scholars also refer to this as national or traditional music.

Iranian Folklore Music

Parallel to the Iranian classical music, there is another category of music. This semi-separate category includes folk songs and music from different regions of Iran. However, many pieces in this category are not necessarily written for the main instruments of Iranian classical music. In addition to the main Instruments of Dastgah – namely Tar, Setar, Ney, Kamancheh, Santour, Qanoon – there exists a vast body of different categories of instruments and the oral tradition of music relating to each one of them. (Refer to The Encyclopedia of Iran’s Instruments in Two volumes, Mohammad Reza Darvishi, Mahoor Publication, Tehran, 2002.)

Iranian Symphonic Music

This category refers to music composed in Iran around the beginning of the twentieth century and after, using Western instruments but deriving ideas such as modes or melodies from Iranian classical music. This style is a hybrid of Iranian classical music and Western classical music. The early examples of this type of music are composed and/or notated by French musicians, who came to Iran to educate the military bands. The instrumentation of this style is often Western orchestral instruments, but some composers have written pieces using the combination of Western symphonic instruments and Iranian instruments. Most Iranian scholars use the term Symphonic music in persian texts. The compositions analyzed in this article belong to this category.

The distinction between these three large categories can be a reference for any performer wanting to play music by Iranian composers. After defining different categories of Iranian music, the next issue facing the performers will be the issue of Identity. What exactly makes music Iranian?

The simplest way to attempt answering this question is to provide examples of how this identity emerges in the music. The music written by an Iranian composer might refer to Iranian/Persian culture in any of the following ways :

- Technical/Theoretical Aspects

- Timbral Aspects – Instrumentation

- Rhythmic Aspects

- Social/Cultural/Historical Aspects

I will try to provide brief examples and resources for each category. Naturally, composers would draw from any of these different pools, most of the time from multiple aspects at the same time.

Technical/Theoretical Aspects

Ornaments, embellishments and any practical techniques that are from Dastgah music (http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/dastgah) or the general canon of the Iranian classical music referred to as Dastgah music.

This category can include a wide range of techniques that Iranian composers include various aspects of Iranian identity in their music. The most prominent uses are compositions based on the theoretical aspects of the Dastgah music and Iranian music theory.

Paj for Flute and Piano (2011) by Saman Samadi is a prominent example of how complex the process of using Iranian modes can be. Samadi writes :

“As a composer who was always fascinated by Western classical music and also knowledgeable in traditional Persian music, I became enthusiastic to acquire an alternate method of pitch organization while using Persian modes that would be acclimated, expressive, and innovative in the context of contemporary classical music. Thus, I formed a method of pitch organization based on the microtonal modes of Persian classical music.” (samansamadi.net)

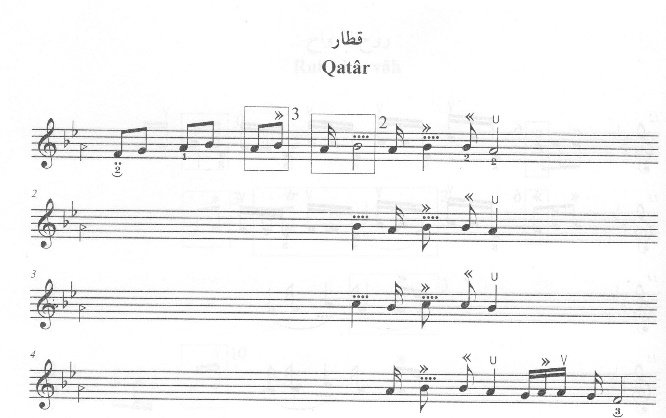

The first example is where Samadi uses a Goosheh (http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/gusa) called Ghatar and redefines the pitch collection into something quite different :

(Listen to the exact moment: https://soundcloud.com/samansamadi/paj#t=7:48)

Ghatar is a smaller component of Bayat-E Tork (http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/bayat-e-tork) and the overall pitch collection of this specific goosheh looks like this :

(Listen: https://open.spotify.com/track/2YGtNUx2LRbvRGShRnrz9H?si=CGDpnyBIRHy6XYuH78OIhA

or https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OW48qkRXBOw )

In addition to the pitch organization, we can also see the melodic contour roughly following the original model as well. From a performer’s point of view, the similarities would directly affect the ornaments, accents and phrasing.

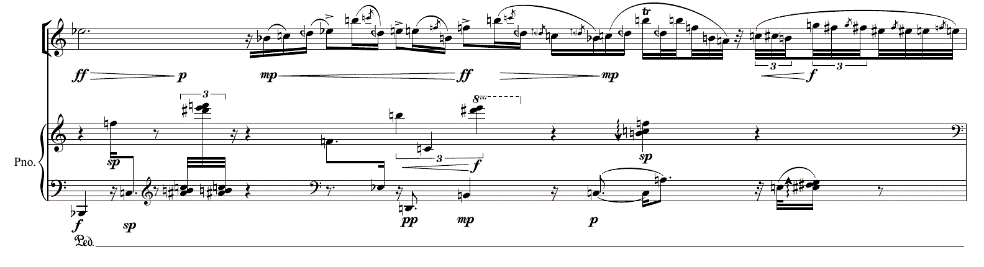

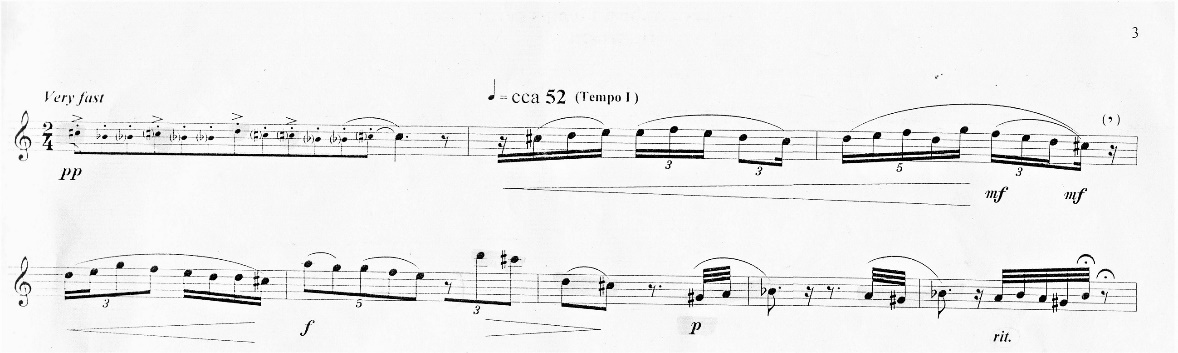

The other example in this category is Amusie for flute and piano (2018) by Kiawasch SahebNassagh. Amusia exemplifies the composer’s lifelong search for the connections between spoken language and music. The overall structure of the piece is a recitative and although he uses complex notation, the result is a free monologue for the flute player augmented with percussive piano chords.

There are examples in Amusie where the composer subconsciously imitates melodic and rhythmic patterns derived from Iranian classical music. As the composer stated in an interview with the author, there is no deliberate plan to have Iranian music patterns. The idea of SahebNassagh unintentionally writing similar patterns to Dastgah music has roots in the connection of Iranian poetry to Iranian classical music. Iranian poetry has influenced SahebNassagh’s creative process. The nature of this poetry is exceptionally rhythmic, and it has ties with Iranian classical music. Amusie uses spoken language as an inspiration to imitate the rhythmical chunks of poetry in the context of the music. All these connections will lead to inevitable similarities in Amusie with motives from Iranian classical music.

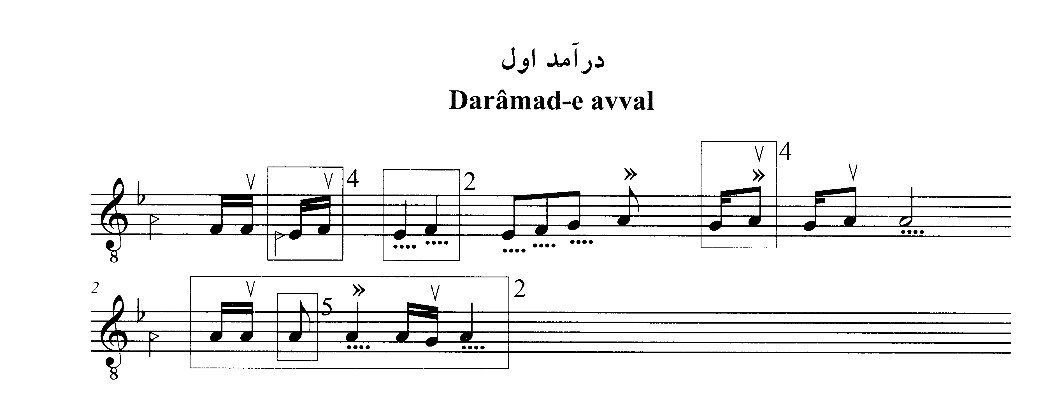

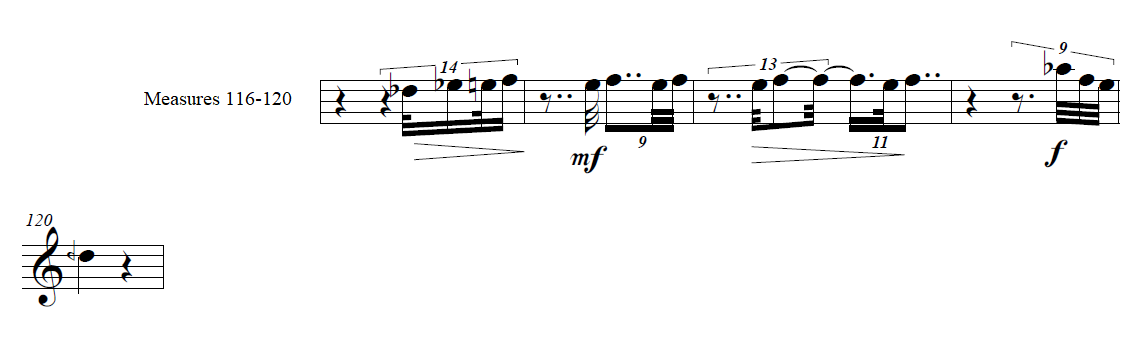

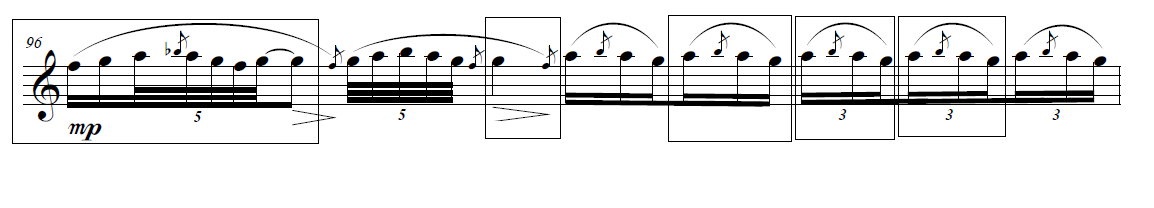

An example of this rhythmic representation comes up in measures 116 to 120. In these measures, the flute line is imitating a traditional Daramad (introduction) in Dastgah music. The overall form of Daramad in Iranian classical music includes an introductory phrase and emphasizing a single note. A lower neighbor tone usually accompanies this main note as an ornament. Here are two examples from Dastgah music. The first one belongs to Dastgah Nava and the second one belongs to the Dastgah Homayoun.

Daramad-e Nava:

Daramad-e Homayoun:

(Dariush Talaie, Radif-e Mirzaabdollah – Analytical Notation (Tehran: Ney Publication, 2013), 183&220)

This is a clear motivic development inspired by Dastgah music introductions in Amusie:

Just like the examples from the context of Iranian classical music, measures 116 starts with an ascending figure to the note F, and then F gets ornamented with a lower neighbor tone, and after that, the melody comes back to the note that started the ascend. The familiarity with the overall sound of the Iranian classical music would drastically change the performance aspects of a complicated piece such as Amusie. An aware performer would aim to create similarities between the piece and its root rather than merely doing the math to provide a mechanically exact performance of the written notation.

Timbral Aspects

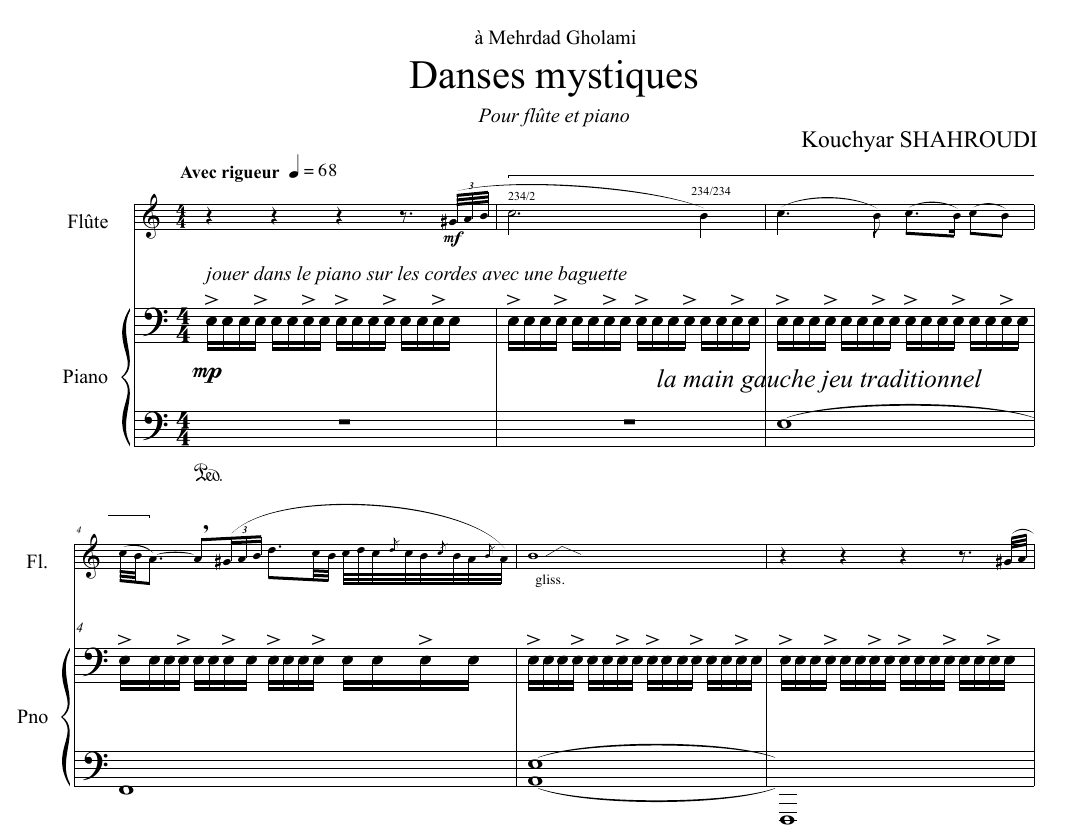

In this category, the composer is trying to evoke the sound quality of Iranian classical music or Iranian folk music. A recurring example would be imitating the sound of an Iranian instrument. Depending on the category of the instruments, this will include a wide range of sonorities. A recent example is the opening of Kouchyar Shahroudi’s Dances Mystiques for flute and piano (2016). Here, Shahroudi changes the nature of both instruments to represent Iranian instruments’ timbre. Flute represents the timbre of ney and the piano, using a wooden stick inside the deck, represents the percussive nature of Iranian santour.

(https://soundcloud.com/mehrdadplaysflute/kouchyar-shahroudi-danses-mystiques-for-flute-and-piano)

The most effective way to understand this category is to gain knowledge about Iranian instruments, their timbre and their aesthetic. This will be more effective if it is paired with a conversation with the composer about the quality of the sound they need. Videos like this on YouTube (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oSp6tAR7DqA) and other sources have made the basic information about the overall quality of Iranian instruments easily accessible. In addition to online sources, for more advanced purposes many sources are offering online lessons and even provide digital books available online. In addition, resources like Garland Encyclopedia of World Music also provides a deeper look into regional sound qualities of Iranian music and beyond.

Rhythmic Aspects

There are many examples where the composer uses rhythmic elements of Iranian music. This can be either from Iranian classical music or Iranian folk music. These appearances of quintessential Iranian rhythms are often very subtle and even to some degree, subconscious.

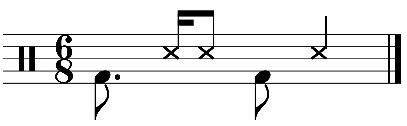

An example of the use of Iranian rhythm is Nastaran Yazdani’s duet for flute and alto flute From Afar (2015). Here the composer has incorporated a very prominent dance-like rhythm from Iranian Dastgah music called the Reng rhythm :

(Performance: https://youtu.be/d9HzLTqo1xg?t=232 at 3:52)

(Listen to a Chahargah Reng by Ali Akbar Shahnazi: http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/tar-reng-chahargah)

In Shahnazi’s performance, the rhythm is over-dotted by the performer, but it is not necessarily written down in the notation. Yazdani’s piece has notated the double-dotted nature of a Reng. Just a simple comparison will add a new layer to the interpretation of the performers and the selection of tempi and note lengths. This is also a good example of hybrid use of Iranian elements. Yazdani uses an Iranian rhythmic motive and at the same time, writes in the vicinity of an Iranian mode, Chahargah. (http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/cahargah)

Chahargah’s sound in this performance can be compared to Yazdani’s representation of the mode as well :

http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/5-04-Dastgah-e-cahargah

Another example of the rhythmic representation of Iranian identity is Mehrdad Pakbaz’s Sonata for flute and guitar (2011). In the third movement, Pakbaz uses one a rhythmical cycle originating in an old rhythmic mode referred to as Iqa (http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/iqa).

(https://youtu.be/Rm9S9tghRAE?t=33)

The dotted lines in m.14 of Pakbaz’s piece indicate groupings that he is using. Like many other examples of Iranian contemporary music, this usage of the rhythmical aspect of Iranian early music is paired with another melody, coming from the context of vocal Dastgah music. The movement is called Gardanieh and the main theme here is the melody of Gardanieh from the Dastgah Nava.

Here you can listen to a version sung by Iranian master Mahmoud Karimi :

https://youtu.be/dLCNxXCh0TY?t=44

Here is the melody in Pakbaz’s piece, much compared to the vocal version :

Social/Cultural/Historical Aspects

Unlike any other categories, this aspect is not necessarily a musically tangible aspect that can be easily measured by musical means. Often composers might draw from an aspect of a cultural phenomenon, or a historical event or even a social movement. Reading the cultural background of the piece might substantially help the performer.

An example of this would be Behzad Ranjbaran’s trio for flute, violin and cello “Fountains of Fin.”

The piece is a combination of many of the aspects discussed before. The composer is specifically asking for flute to imitate the timbre of ney, the rhythms in the middle section represent an Iranian classical music dance and the harmony evokes the Iranian mode Isfahan. (http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/bayat-e-esfahan(

The title of the piece refers to a garden located in central Iran. In Addition to its historical significance, this place has hosted one of Iran’s most important political events of the past two centuries which is the assassination of Amir Kabir. (http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/amir-e-kabir-mirza-taqi-khan)

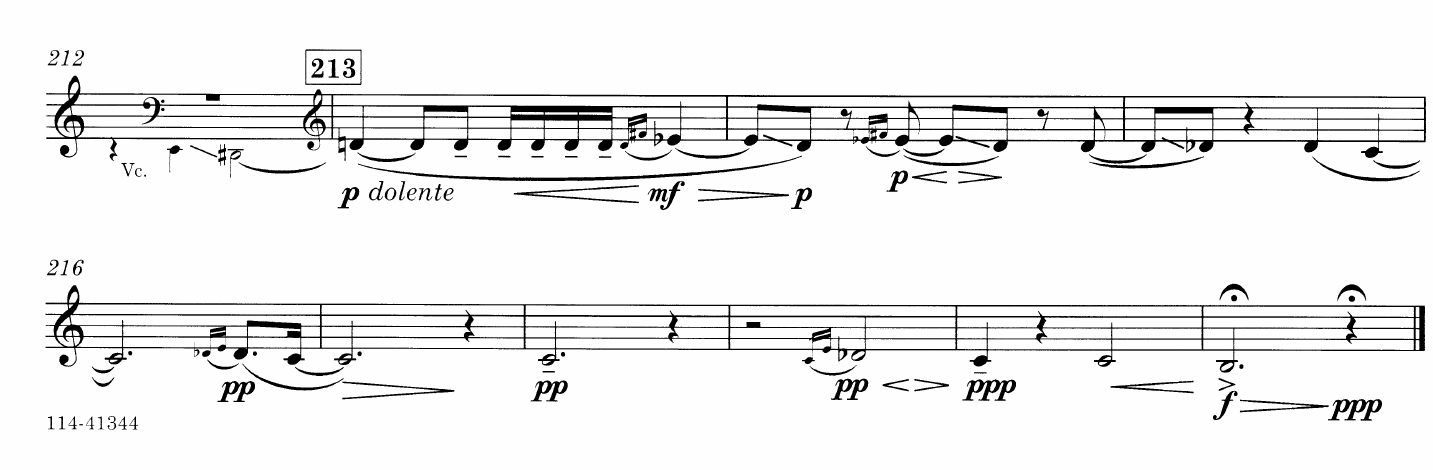

Unfolding all these inner layers will help the performer to present a better interpretation. By considering all the mentioned Iranian influences, the performer should interpret the ending phrase on the flute differently. Here, the flute is evoking Nay, so the timbre is played hollower. The flute also represents Amir Kabir’s last moments. Also, knowing the way he was assassinated will completely change this section’s interpretation :

Hybrid Representation

Most pieces in the previous category are a combination of different representations of an Iranian element in a piece written for a western instrument. As we try to build boundaries about the nature of this fluid definition of identity, there are many examples to prove us wrong. In many cases, the composer will combine elements of Iranian music with other sources of inspiration. In a short solo flute piece, written originally for piano, Alireza Mashayekhi (b.1940) draws from two distinct sources. One, the composer’s fascination with Marcel Proust’s book, In Search of Lost Time, and the other, Iranian Folk music. Here an Iranian folk melody, Dokhtar-e Boyr Ahmadi, comes back multiple times in piece written with Proust’s style of stream of consciousness.

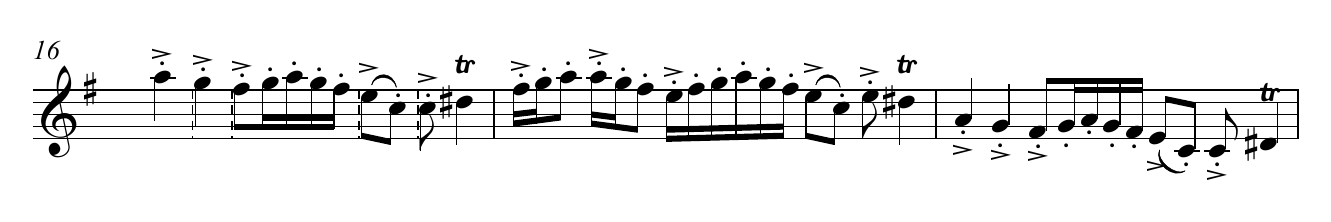

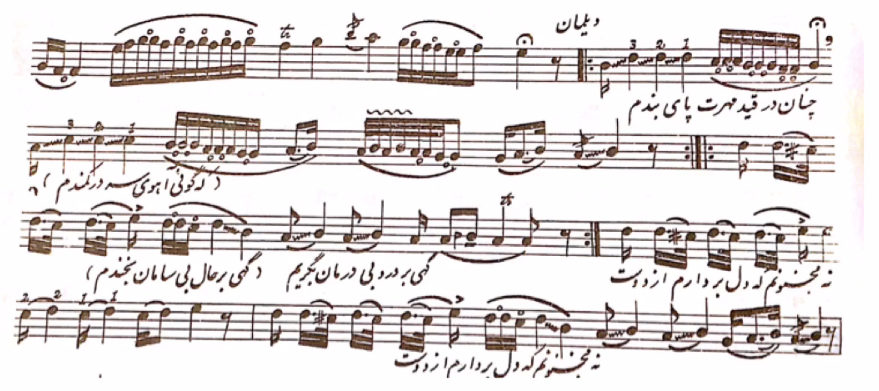

Another example in this category is Kouchyar Shahroudi’s Dance Mystiques where the composer has used a folk melody while incorporating the ney ornaments in the melody. Deylaman, is a folk melody from a region in northern Iran, a region with the same name that has entered the body of radif (the sequence of each Dastgah) by Abolhasan Saba (1902-1957), a prominent Iranian classical music master. This Goosheh is one of the subordinates of a larger structure called Avaz-e Dashti. The following example is the notation Abolhasan Saba used in his method for Iranian violin playing.[1] Saba notated the structure of the melody, and the notation does not specify the meter or time signature. The text of the melody is a sonnet by the thirteenth-century Iranian poet, Sa’di Shirazi (1210-1291).

Abolhasan Saba’s transcription of Deylaman vs Shahroudi’s version

One of the earliest examples of setting Deylaman on a rhythmic accompaniment is performed in a recording of the Golha radio program from Iran’s National Radio. The Golha (literally, Flowers) music series was produced by Iranian National Radio for 23 years from 1956 to 1979. (Lewisohn, Jane. “The Golha Programmes.” Http://www.golha.co.uk. http://www.golha.co.uk/en/about/programmes#.XEU5IVxKg2y) It seems the inspiration of setting Deylaman to a context of piano accompaniment and a wind instrument comes from this program.

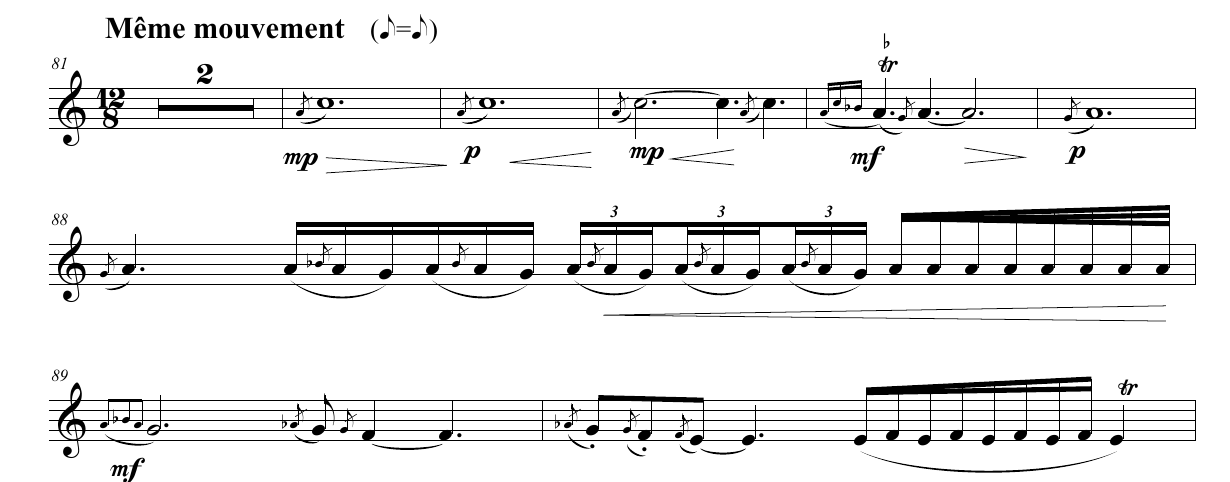

The composer develops this simple melody into a virtuosic flute passage by the end of this section (measure 103). These virtuosic passages demonstrate a chromatic treatment of the theme that reflects the composer’s Western composition training, and at the same time, they use Iranian classical music ornaments like Tekieh and Eshareh.

Example of the chromatic treatment of the Iranian melody, Deylaman:

Example of using Iranian ornaments tekieh and eshareh:

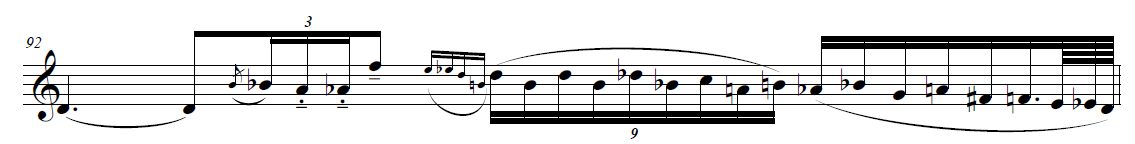

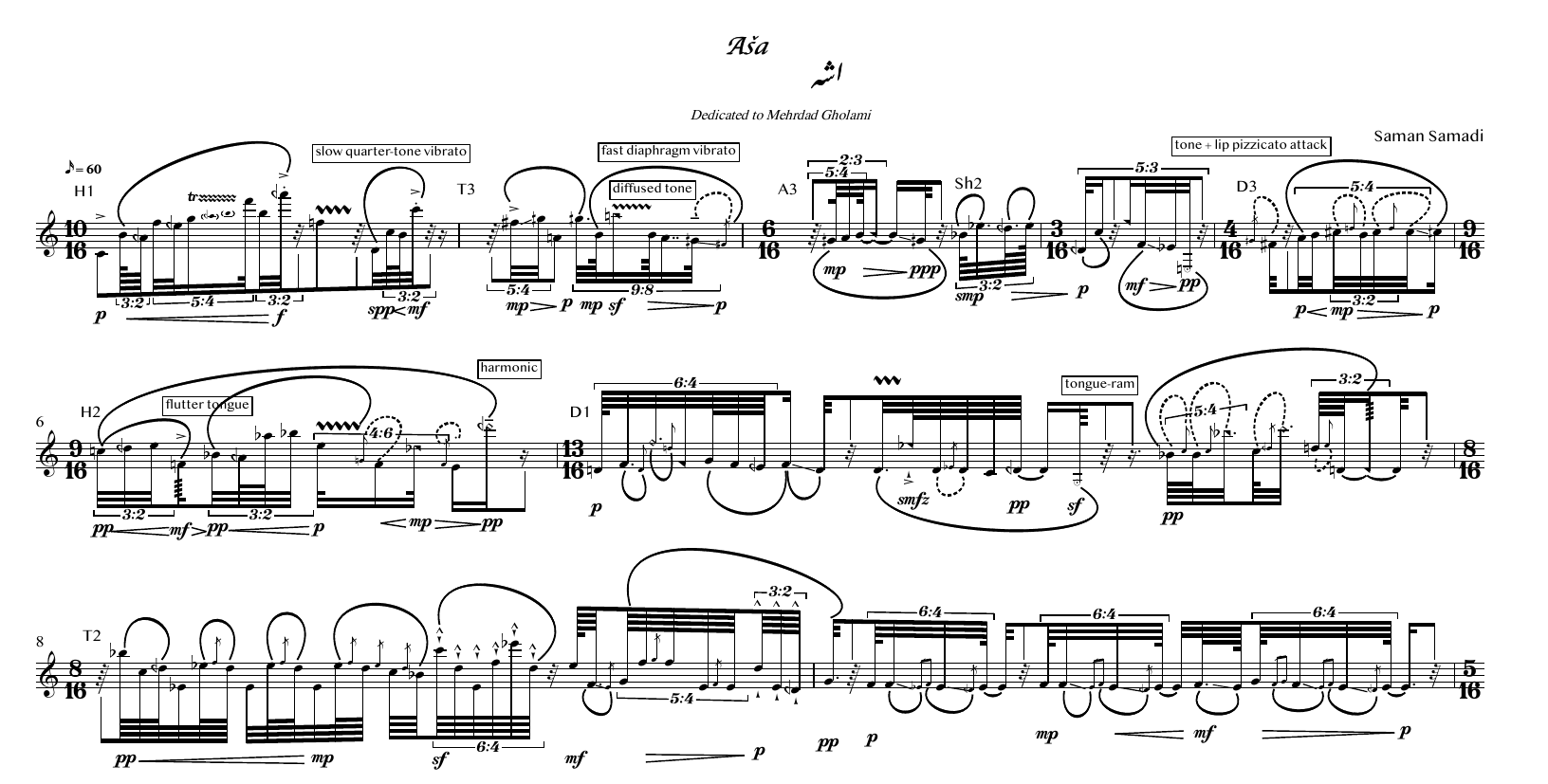

The most recent example of a hybrid of Iranian influences is Saman Samadi’s newest piece for solo flute “Asha” (2020). Here, the composer is using an old Zoroastrian word AṦA (http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/asa-means-truth-in-avestan?fbclid=IwAR06CjPcAcYujfcRJKbx_5LQ5FPtZKtRQlVqHl-9dBZRUzUpfnsICzFPIJk ) as the basis of the piece. This is paired with his unique style of morphing Iranian classical music into the western equivalent of neo-complexity notation. Here the composer is “forcing” the performer to be accurate with the ornaments, often resembling those played on ney. In addition to the cultural influences of the piece, we can see the Iranian classical music ornaments and theoretical aspects all at once.

With the recent technological advances and the presence of social media, accessing information about any subject has become much easier. Performers, depending on the piece they are playing, can easily write to the composer, read about the background of the piece, listen to a podcast or look up a free access encyclopedia to have a deeper understanding of the piece they are playing.

Resources like Encyclopedia Iranica (http://www.iranicaonline.org/) are among the most trusted sources of information to access fast, reliable, scholarly information about different aspects of Persian culture inside and outside of Iran. Paired with less scholarly but more accessible tools such as YouTube and other types of social media, the combination can provide a level of understanding of the underlying concept of each given piece. The biggest factor here might only be the eagerness to ask questions, explore and learn.

- Rahmatollah Badiee, Doreye Ali-e Violin, Maktab-e Saba (Advanced Violin Method, Saba’s School) (Tehran: Soroud Pulication, 1994), 46. ↑