Electroacoustic Music in Iran

Creation, History, Transformation, Revolutions

Introduction

Music in Iran is an art discipline with different levels of understanding and specific complexity with a rich tradition evidenced by ancient testimonies, archaeological documents, written statements or literary references in poetry and prose. It has survived several waves of rejection and acceptance over the millennia of rule under caliphates, monarchies or the current regime[1]. This has given it a unique shape and means that understanding the complexity of music in Iran has always been closely linked to a consideration of national history and political and religious influences within the country.

Originally, European music arrived in Iran during the reign of the Qajar dynasty in the late 19th century and represented the ruler’s urge to redefine Iranian music by making it resemble the Western tradition[2]. The 20th century became a time of extensive globalisation and the introduction of capitalism and consumerism into all parameters of modern life. With its strong individual characteristics and outstanding cultural heritage, Iranian art has embraced cultural change and absorbed Western art trends, creating an unprecedented new generation of art in Iran[3]. The musical diversity of existing genres has expanded, giving rise to the categories of classical, Iranian classical and popular music, which in some ways remain completely new to Iranian society to this day, in addition to traditional and folk music, which have always represented the true musical face of the country.

Electroacoustic music in Iran has become one of the most vibrant and interesting musical genres to have developed in recent decades. This text is a brief study that presents the emergence, history, change, rebirth and current situation of selected movements and important works of electroacoustic music in Iran and the diaspora from a historical and socio-political perspective. I encourage anyone interested in further exploring this topic to look at the references listed in my work and immerse themselves in the vast and fascinating world of Iranian electroacoustic music.

Alireza Mashayekhi, the Pioneer of Electroacoustic Music in Iran

It is very hard to point out a concrete date when electronic music found its way to Iran. Most sources say that this musical genre emerged in Iran in the 1960s[4]. That is, the first Iranian composers began creating electronic music in the 1960s while studying and working outside Iran, however, the first electroacoustic music concert in Iran occurred in 1971 in Persepolis[5]. During the reign of Reza Shah[6], the first ruler of the Pahlavi dynasty, the country underwent radical modernisation in politics, culture and society. Reza Shah decided to reform Iran to become more like Western countries, inspired by the deeds of his contemporary Mustafa Kemal Atatürk and modernisation of Turkey[7]. “The industrial drive of the 1920s and 1930s was strongly supported by the young, Western-educated, and reformist people who backed Reza Shah”[8]. The Shah sent students abroad for technological training, creating a base of highly skilled Iranian scientists, engineers and artists. This trend of promoting and training promising Iranians abroad continued until the end of the monarchy in 1978[9].

Alireza Mashayekhi, the first Iranian composer to work in a genre of electroacoustic music, was born in Tehran in 1940 and came into contact with music at a very early age. When Mashayekhi took private lessons in Iranian music with Lotfollah Mofakham-Payan, his teacher soon recognised his student’s compositional talent and encouraged him to study composition[10]. Mashayekhi’s desire to “discover new elements [in music]”[11] soon turned into an active pursuit in the arts, leading to his admission to the Academy of Music and Performing Arts in Vienna. Around 1957 or 1958, the future composer left Iran to continue his education in Austria[12]. Fascinated by the techniques of dodecaphony and the ideas of the Second Viennese School, he began to attend Hanns Jelinek’s composition class. As he recalls, the first example of electronic music he approached was Jelinek’s film music, followed by his discovery of the works of Herbert Eimert, Pierre Schaeffer, Gotfried Michael Koening and finally, Karlheinz Stockhausen[13]. After graduating, Mashayekhi continued his studies in electronic and computer music at the University of Utrecht in the Netherlands[14]. His mentor became Gottfried Michael Koenig, a German-Dutch composer who preferred relying on technicians’ knowledge to solve an electronic problem rather than letting the composers become technicians. In this way, Mashayekhi admired the freedom of musical expression when working in the studio and could benefit from the guidance of studio technicians when approaching a significant technical problem.[15]/[16]

Although sources indicate that Alireza Mashayekhi’s first electronic compositions date from 1965[17], there is no evidence of earlier works by the title. His first official electronic composition, Shur op.15, is completed in 1968[18] and released in 1970 on the vinyl compilation “Electronic Panorama”, featuring electronic music from electronic music studios in Utrecht, Warsaw, Tokyo and Paris[19]. In Shur, the composer stretches the harmonic structures of a violin melody and creates a dialogue through delay and multiple repetitions of the material. It is not a simple collage of musical elements, but Mashayekhi, true to his compositional statements, seeks a higher order of organisation of the musical material to achieve a “newity”[20] in sound. The presence of Persian musical traditions is clearly evident in this work. The violin material was created with the help of the Iranian violinist Houshang Taheri[21].

After graduating from the University of Utrecht, Mashayekhi returned to Iran and became a member of the composition faculty at the University of Tehran in 1970.[22] However, in his 2006 interview with Bob Gluck, the composer mentions:

“When I started to encourage young music students to pursue new music, there were no electronic studios in Tehran. I had just finished Shur […]. At that time I started to teach twelve-tone music to some of my students, among them Mr. Dariush Dolat-Shahi.”[23]

Mashayekhi explains that the use of computers, electronic sounds and Iranian musical heritage can serve as a trigger for the construction of a new language[24], which also explains his interest in combining different multicultural elements. The impressive number of purely electronic, electroacoustic or mixed compositions in the composer’s portfolio[25] and the creation of an elaborate concept to combine Western music with local musical heritage mark the beginning of an electroacoustic music presence in Iran. Mashayekhi soon became a key mentor and academic collaborator, guiding and training future generations of Iranian composers. Many of the composers mentioned in this text are his former students.

Alireza Mashayekhi – East-West op. 45 (1973)

Dariush Dolatshahi and Iranian Electroacoustic Composers in 1970s

Dariush Dolatshahi[26], a ten-year-old boy from Tehran and future renowned composer of electroacoustic music, is sent by his parents to the “Music Academy” for music lessons in 1957[27]. In 1965, he enrolled to study composition at the University of Tehran and received a thorough musical education, especially under the guidance of Thomas Christian David (Western music and composition), Aliakbar Shahnazi (Tar), Nurali Burumand (Iranian music) or Habibollah Salehi (Iranian music and composition) among others[28]. Nevertheless, he does not remember being introduced to electronic music at that time:

“In Iran, I had been a part of a group of four people who used to get together and listen to music by Schoenberg, Berg, Ligeti… but not specifically electronic compositions. If I had heard any electronic music before being in Holland, I don’t remember that it had any significance to me.”[29]

Dolatshahi admits, however, that he recorded his first electronic work for tape and string quartet/string ensemble with a Groendig tape recorder before going to Holland to study in 1970.[30] As he puts it:

“It was really a test with sounds and not a composition […]. It was kind of an introduction to electronic music for me. […] I had not been aware of electronic music before that.”[31]

As documented in an interview by Bob Gluck, based on conversations from 2005, Dolatshahi constructed the electronic part of this work by recording material on one channel and playing the music back while recording new material on the other channel[32]. This composition was probably made between 1967-70, when Dolatshahi graduated from the University of Tehran (1968) and joined the army’s music department, where he led the band until 1970[33]. Unfortunately, there is no other source or audio documentation of these experiments.

In 1970, the composer left Iran to study electronic music at the University of Utrecht with Gottfried Michael Koenig, thanks to a scholarship from the Iranian government. As he recalls, the time spent in Holland is not what he expected:

“Studying in Utrecht wasn’t what I expected. I thought that I would immediately begin composing. But you first had to study acoustics, which didn’t interest me. I don’t have a scientific mind. Eventually when we finally began working with sound, I became more interested.”[34]

Dolatshahi spent four years of his education in Holland. The tape material for the works Two Movements for string orchestra and Mirage for orchestra was created in the studio in Utrecht[35]. After graduating, the composer returned to Iran and began teaching composition at Tehran University[36], but still believed he could learn more. He inquired about a possible place at Columbia University, and after receiving another scholarship from the Iranian government, he began a doctorate in electronic music at the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center in 1976[37]. After arriving in New York in 1975, Dolatshahi studied with Dr. Hubert S. Howe, Jr. at Queens College[38] for about nine months. He immersed himself in the world of keyboards and synthesisers and developed his first small pieces. When he began a doctorate at Columbia-Princeton in 1976, his teachers, including Vladimir Ussachevski, Mario Davidovsky, Alice Shields and Pril Smiley, were the source of great inspiration in electroacoustic research and philosophy of art, as they praised the variety, openness and diversity of teaching approaches. As Dolatshahi recalls:

“Every year we had a three-day group of electronic music concerts at Columbia. I usually had a piece performed. In addition to that, there were concerts organized by other organizations and played at different places in New York City.”[39]

Unfortunately, there are no sound documents from Dolatshahi’s student days, but the composer will mark his position in the electroacoustic music scene of the early 1980s with true masterpieces of electronic art, musique concrète thinking and Iranian cultural heritage.

One Iranian composer followed the path of electronic music in a completely separate way than his Iranian colleagues. Shahrokh Khajenouri was born in Tehran in 1952. He began his musical education in a piano class taught by Emanuel Melik Aslanian and moved to England in 1971[40]. He completed his academic music training in various institutions and specializations, including composition studies at the London Academy of Music and electronic music studies at Morley College of London with Michael Graubart[41]. He is known for his in-depth experimentation with musique concrète techniques as well as his use of analogue synthesisers (VCS3)[42]. One of the most important compositions from this period is Three Movements for Concrete Electronic Music from 1978.[43].

The Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center was an oasis of knowledge for two other Iranian composers who also received their scholarship from the Iranian government: Ahmad Pejman and Massoud Pourfarrokh, both of whom studied during the period 1977-1978. The CPEMC documentation says: “Two young Iranian composers heard electronic works from Europe and the U.S. in Iran but lacked any studio experience […].”[44] Pejman was not interested in pursuing electronic music, but he found an experience with several synthesisers and electronic equipment helped him develop his career in the film industry and became one of Iran’s most prominent film music composers[45]. The CPEMC report says: “Ahmad Pejman found CPEMC aesthetically not to his liking and continued his work independently in more orchestral commercial directions, in Iran and the United States.” Massoud Pourfarrokh was probably the least fortunate of the Iranian exchange students. With no previous experience, he was forced to give up composing at the beginning of his eventual path in electronic music because he found no support in the United States, especially after the events of 1979 in Iran. There is no documentation of his musical activities. Until his untimely death in 1997, he contributed mainly to the improvement of the Oriental section of the New York Public Library.[46]

Around Shiraz Arts Festival

One of the most important events that drew attention to Iran as a centre of the international cultural scene in the 20th century was the establishment of the Shiraz Arts Festival, or sometimes called Jashn-e Honar-e Shiraz[47], a major international feast of the arts that lasted until 1977. “The 1967 establishment of a Festival of Arts at Persepolis and the nearby university city of Shiraz simultaneously provided the historical linkage and the desire of the Empress Farah Diba[…] to showcase the cultural enlightenment of her country.”[48] The Empress of Iran was the spiritus movens in organising the festival. Her artistic taste reflected the programme of each edition, while the formal organisation of the festival was the responsibility of the National Iranian Radio and Television (NIRT)[49]. Sheherazade (Afshar) Ghotbi, a violinist and wife of NIRT director Reza Ghotbi, was appointed musical director of the festival and, together with her husband, established “a coalition of like-minded Iranian cultural practitioners”[50]/[51], responsible for the main content of the annual festival programmes. The main aim of the Shiraz Arts Festival was to create a meeting place for the arts, a special event for cultural exchange that contributes to the promotion of traditional and modern Persian art worldwide, while introducing traditional and often avant-garde foreign art to Iranian society.

The festival sparked much controversy as it highlighted a radical contrast between the cultural norms of Iranian society and Western thought that some Iranians were not yet prepared for. It is important to point out here the modernisation of Iran started by Reza Shah and continued by his successor Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, who wanted to show Iran in a fully westernised form. In a way, the Shah wanted to prove the modernity and openness of the country in all spheres of life, which were often in stark contrast to the reality of life and traditional values in Iran. In addition, the worsening economic crisis in Iran and the deterioration of living conditions and freedoms of Iranian citizens[52] were some of the other factors that disturbed public opinion and international thinking about organising such a costly cultural event, which perhaps indirectly, but also eventually, contributed to the dramatic events in Iranian history that led to the Islamic Revolution of 1978/1979.

Among the many artistic events and the diversity of the programme of the Shiraz Arts Festival, electroacoustic music has also presented itself to the Iranian audience. Iannis Xenakis (1922-2001) is by far the most important composer who brought his compositional vision to life during the Festival in Persepolis. Although his acoustic pieces have been performed since 1968 and many of them already contained elements of inspiration from Persian art and heritage, it is the 5th Shiraz Arts Festival where Xenakis’s electroacoustic music will finally be performed. What Robert Gluck describes as “the multimedia extravaganza”[53], Polytope de Persépolis or simply Persépolis, was a huge multimedia work commissioned by the Shiraz Arts Festival to mark the 2500th anniversary of the founding of Iran by Cyrus the Great in 1971. It opened the Festival on 26 August along with the introductory piece Diamorphoses, considered the first work Xenakis created entirely in musique concrète technique (completed in 1958)[54]. Persépolis is a work that contains both spectacle and music. The performance required the installation of 59 loudspeakers, 92 spotlights and 2 lasers spatially distributed throughout the ruins of Persepolis, with additional bonfires and children’s parades that resembled linear patterns from the audience’s perspective[55]. The piece was also a great challenge from a musical point of view:

“According to his sketches, Xenakis constructed the tape from 11 sonic entities distributed among the eight channels. […] The performance would have required two 8-track machines so that the piece could be performed with no breaks. Multiple layers of similar material create overall textural <<zones>> which serve to delineate the form, though the shifts from one to another are rarely easy to distinguish.”[56]

It is also documented that Xenakis himself directed the premiere of Persépolis from a control desk via a walkie-talkie[57]. The performance provoked many mixed reactions, but it nevertheless opened the way for Xenakis to international recognition in the art world.

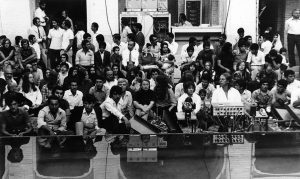

Iannis Xenakis preparing for the performance of his Persépolis in 1971, Persepolis Ruins, Iran.

The 1972 edition of the Shiraz Arts Festival was entirely dedicated to the music of Karlheinz Stockhausen, a so-called “Stockhausen Panorama”, which is probably one of the most experimental editions in terms of presenting electroacoustic music. During the week from 31 August to 8 September 1972, more than 15 works by Stockhausen could be heard live or as tape recordings, including Mantra, Hymnen, Kontakte or the famous Gesang der Jünglinge to name but a few. Electroacoustic works from Italy, USA, Poland, Croatia or Japan were also heard at the Festival’s events, but above all the music of contemporary Iranian composers had an important place in the repertoire from the very beginning. Many new Iranian works were included in the programmes together with Western classical music[58], which was an original and bold approach to the curatorial practise of the festival board and introduced the inclusion of Western and Iranian music in the same events. The music of Iranian composers heard at the festival was mostly acoustic in origin. Although some sources claim[59] that Alireza Mashayekhi’s electronic piece Shur was performed during the 1977 Shiraz Arts Festival, there is no reliable documentation to confirm this event. Mashayekhi’s music had been included in the festival’s programmes since 1974[60], but the composer boycotted these events and criticised the organisers of the Shiraz Arts Festival, pointing out its “destructive impact due to the totally Western focus and opportunism on the part of some visiting composers that did not advance the cause of Iranian composers.”[61]

The tenth edition of the Shiraz Arts Festival presents the first electroacoustic works by Iranian composers. Dariush Dolatshahi, whose acoustic music had already been performed in 1971 and 1973[62], was commissioned by the National Iranian Radio and Television (NIRT) to compose a piece for chamber orchestra and electronics, which was performed as part of the festival programme in 1976. The composition From behind the Glass, performed on 20 August 1976 by the NIRT orchestra conducted by Ivo Malec, was a work for twenty strings, piano, tape and echo system. The electronic part of this work was composed at the Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center, where Dolatshahi began his studies in 1976[63]. The Tehran Journal review stated that this composition “conveyed a stimulating imagination of space, was original and good to listen to”[64]. Information on the dating and performance of Dolatshahi’s early works seems to be very inconsistent. Some sources give information about the work Mirage for orchestra and tape and even refer to reviews by the Tehran Journal from 1977[65], but I have not been able to find any further information about this work, nor did the composer comment on it when I contacted him.

Karlheinz Stockhausen at Seraye Moshir in Shiraz, 2 September 1972.

Another Iranian composer frequently performed during the festival is Fozié Majd[66], Iran’s first successful woman composer, an acclaimed ethnomusicologist and advisor to the Shiraz Arts Festival programming team[67]. In addition to several acoustic compositions and the screening of two films for which she wrote the music[68], a theatre play entitled There Appeared a Knight with a Red Face, Red Hair, Red Lips, Red Teeth, a Red Gown, a Red Horse, a Red Spear… is worth mentioning. This play, based on Persian mystical literature, with a text by Mahin Jahanbeglou Tajadod and the creation and direction of Arby Ovanessian, was commissioned by the 10th Shiraz Arts Festival and performed from 22 to 24 and 26 to 28 August 1976. This work is unique for several reasons. This production is the first collectively created play in Iran[69], a tradition introduced to Iran through Western theatre practise. Moreover, musically, layers of the play contain different sources of expression. While there are many traditionally sung parts in the narration of the play, usually based on folk melodies collected by Majd[70], and then arranged and taught to the actors, the play contains three short fragments of tape music that together form a trilogy entitled Songs of Separation.

The Songs of Separation are the first surviving example of a musique concrète composition by an Iranian composer. Three short compositions: Faraqi, The Song of Qamar and O Child! O Yes! were originally made in 1973, and Fozié Majd worked on them together with Fereydun Danai, the sound engineer of NIRTV at the time. As Majd recalls:

“I prepared several pieces taking the music material from the recordings made while travelling through the province of Khorasan, its towns and multitude of scattered villages. […] Here, chosen phrases and motifs are superimposed into a collage.”[71]

Electronic music at the Shiraz Arts Festival was last performed in 1976. The political situation in Iran was becoming increasingly tense, the atmosphere of growing protests and society’s discontent with the Shah’s rule increasing with each passing month. Iannis Xenakis, probably the most important electronic composer at the Shiraz Arts Festival, had to withdraw from the festival with a heavy heart and a lengthy explanation:

“…faced with inhuman and unnecessary police repression that the Shah and his government are inflicting on Iran’s youth, I am incapable of lending any moral guarantee, regardless of how fragile that may be, since it is a matter of artist creation.”[72]

The gap between rich and poor widened, an oil war and political games flourished, and the voice of Ruhallah Khomeini, the leader of the revolutionary movement, lent increasing strength to protests against the Shah’s regime[73]. The organisation of the Shiraz Arts Festival, as well as the presentation of artistic events that were in any way connected to Western culture, became increasingly problematic in execution, leading to the cancellation of the 1978 edition[74] of the festival, followed by the 1979 Islamic Revolution and the collapse of artistic development in Iran for several decades.

The Dark Interlude

The political situation in Iran became more and more difficult, one could feel the rising tensions in all major Iranian cities, and Tehran became a ticking bomb whose inhabitants poured into the streets to show their disappointment with the government’s actions[75]. The Iranian artistic community began to feel insecure. The organisation of the Shiraz Arts Festival became hard, many famous artists began to boycott the event and refused to participate in the 1976 and 1977 editions after information about the Shah’s police brutality towards Iranian demonstrators became public[76]. Many foreign musicians working in Tehran realised that it was no longer safe to live in Iran. Dolatshahi recalls, “In 1975-1976, people who knew better began to return to their original countries, knowing that the coming political conflicts were beginning to happen”[77]. Mohammad Reza Shah himself, trying until the last moment to keep a stony face and pretend that the situation was under control, finally fled the country with his entire family on 17 January 1979[78]. After these events, Ruhallah Khomeini returned victoriously to Tehran in an Air France chartered plane, accompanied by 120 journalists on board, and finally set foot on domestic soil again on 1 February 1979. Shortly afterwards, on 11 February 1979, Mohammad Reza Shah was officially overthrown and the Islamic Revolution reached its climax[79].

The situation in Iran will never be the same as it was before the Islamic Revolution of 1979. Music became the enemy of the nation and superfluous in the eyes of the new regime. Shortly after the Islamic Revolution, a ban on performing and listening to music was issued by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. The justification for this ban, issued on 23 July 1979, was, according to the supreme leader, that music is “no different from opium”[80] and it “stupefies persons listening to it and makes their brain inactive and frivolous”[81]. From that moment on, all music institutes were closed, including the music department of Tehran University. The lives of musicians were in constant danger, as all activities related to music were strictly forbidden under threat of imprisonment – making music, teaching music, owning musical instruments at home, or any other behaviour that might raise suspicions about the spread of music in society. Although music no longer officially existed in Iran, the black market flourished in the 1980s. Just as Khomeini used cassettes as a propaganda tool before the revolution[82] to disseminate speeches and convey messages while he was outside the country, this time the cassettes contained different material. Western popular music circulated on cassettes and LPs smuggled into Iran by ordinary people. The need to keep sane in the times of war and post-revolutionary oppression of Iranian society meant that music was valued as forbidden fruit. Even the electronic artist Sote admitted that as a child in Iran he came into contact with many smuggled cassette tapes:

“I got exposed to things like Culture Club and Duran Duran. Some people are drawn to lyrics, some people are drawn to melodies. When I listened to Duran Duran I would always keep rewinding to the weird sweeps of synthesizers.”[83]

Iranians had access to the widely recopied material and distributed it among themselves. The music of Led Zeppelin, Pink Floyd, David Bowie[84] and many other stars of the 1980s reached the young generation of Iranians in the underground and kept them up to date with international music trends.

Electronic Music, Tar and Setar and Otashgah

On the other side of the globe, in the United States, Dariush Dolatshahi stayed on the new continent and developed his musical skills. He earned a doctorate in electronic music from Columbia-Princeton in 1981 and continued to use the university’s studios for several years[85]. Although there was no longer any government financial support from Iran for his stay in the United States, the composer managed to live and work as a musician in New York. In the 1980s, he composed his greatest surviving masterpieces of electroacoustic music, which were released consecutively on two vinyl releases by Folkways Records[86] in 1985 and 1986.

A publication entitled Electronic Music, Tar and Setar contained five compositions Dolatshahi made in the early 1980s: Samā’, Hūr, Zahāb and Razm are composed for tar and electronics, while Shabistān is a work for setar and electronics. The compositions are among the first electroacoustic works to use a traditional Iranian instrument in an experimental setting[87]. The composer, himself a tar virtuoso, recorded all the musical material. Inspired by the Sufi traditions, he sought “to attain the balance of electronic abstraction and traditional spiritualism”[88]. According to the record’s booklet, all the compositions on this compilation were presented by Dolatshahi during a concert at Carnegie Recital Hall in December 1983. The works emphasise the role of balance between the sonic subtlety of traditional Iranian instruments with its improvisatory melodic treatment and the accompanying role of electronics. Delicate, repetitive synthesiser sounds, bird motifs or percussive tonbak structures entwine the instrumental improvisations, creating a musical landscape of meditative yet vibrant motivic structures. Dolatshahi explained that his approach to composing music is very eclectic, a certain combination of traditional and contemporary. The composer recalled working on Electronic Music, Tar and Setar and confessed:

“While the instrumental pieces that I did at that point remained in line with the abstract, serial Columbia style, the electronic music equipment allowed me to express another part of myself. Working mostly on my own, I became involved in a more expressionist style. I let it out”[89].

The two-part masterpiece Otashgah (which means “place of fire” in Persian) was composed at Stony Brook University’s Electronic Music Studio in 1985. Dolatshahi’s epic work is inspired by the story of the discovery of fire described by the poet Ferdowsi in Persia’s most important literary work, Shahnameh. The composition is in some ways a continuation of the philosophy and soundscape presented on the first vinyl release, but this time without the element of traditional Iranian instruments. The listener is drowning in maddeningly repetitive melodic threads, rhythmic shifts and contrasting material eruptions of analogue sounds. As Perry Goldstein concludes, Dolatshahi “has given voice to his traditional cultural values, not by avoiding technology but by confronting it. Perhaps it is the spark created by these inimical colliding forces that gives the music some of its life.”[90] This composition is undoubtedly one of the most important works of art in Iranian electroacoustic music.

1990s – 2013s Thaw

According to Malihe Maghazei, citing Mehdi Semati’s research[91], the status of music after the 1979 Islamic Revolution can be described in four phases: “the first stage (1979-1988), when the revolutionary social atmosphere was guided by Ayatollah Khomeini […]; the reconstruction era (1989-1997) led by Ali Akbar Rafsanjani; the reform years (1997-2005) led by Mohammad Khatami and finally the repressive period (2005-2013) headed by Mahmoud Ahmadinejad”.[92] The period from 1979 to 1989 can undoubtedly be described as a time of stagnation in Iranian cultural history and has already been briefly described in an earlier section. The post-war period slowly brought about a change in society through a slow but steady revival in the field of art. Moreover, after a ten-year hiatus, “the Music Department of Tehran University [got] re-opened, now emphasizing on theoretical aspects of music”[93]. The unfortunate part of this situation was the fact that during the ten years of the ban on any musical activity in Iran, except for war and religious propaganda music, there were hardly any highly qualified music teachers in the country to help with the growing acceptance of music after the war. Most of the prominent musicians of the 1970s fled the country during the revolutionary and war years, or some of them gave up their music careers and devoted themselves to other work. In this situation, the world of Iranian music had to be rebuilt from scratch.

Alireza Mashayekhi once again contributes to the revival of the Iranian music scene. He returns to the country from Europe in the mid-1980s, later to take up another post at the University of Tehran. His primary goal, however, is to create a private education programme for Iranians, with “an ideological dream of fostering <<1000 composers in Iran>>“[94]. His private composition classes became exclusive and difficult to access gatherings for the selected students. Many Iranians who wanted to attend Mashayekhi’s courses even had to wait for years to be admitted – some ended up not getting a chance to be admitted at all. Although driven by his own personal agenda and the need to perform his own compositions, Alireza Mashayekhi founded the Tehran Contemporary Music Group with pianist and teacher Farimah Ghavamsadri[95] in 1993 and the Iranian Orchestra for New Music in 1995. The spark of change and the growing accessibility to contemporary music is still confined to the Iranian capital Tehran. The development of electroacoustic music is quite limited in the country, despite a leading artist like Mashayekhi, due to the lack of a technical base: professional electronic music studios, private studios and electronic equipment. Many Iranians, driven by the urge to make music, start learning it independently and without teachers, forming underground communities and experimenting on their own. With the election of the reformist politician Mohammad Khatami as the new president of the Islamic Republic of Iran in May 1997 and the general easing of restrictions imposed by the regime in the areas of culture, art and censorship, the scene of contemporary Iranian music is developing again.

Given the elitist educational model of knowledge transmission in the country and the individual practises of the rest of the academics, one can observe the rapid development of electroacoustic music in two opposite directions. The select Iranians admitted to the University of Tehran, or Alireza Mashayekhi’s students, form the academic movement of contemporary and electroacoustic music, which resembles the lineage of contemporary classical and academic creation in this genre. The others, with their experimental practises and independent experiments, soon form the ground for the development of what is known as intelligent dance music or electronic dance music, a basis for an extremely vibrant and diverse experimental electronic music scene of Iran.[96]

Most of Mashayekhi’s students left Iran to continue their musical education in Europe or the United States, the vast majority never returning. However, the electroacoustic composer Kiawasch Saahebnassagh (b. 1968), a graduate of the University of Music and Dramatic Arts in Graz[97], returned in 2006[98] to assist his former teacher at the University of Tehran as an academic collaborator. Other notable student of Mashayekhi who has made a name for himself as electroacoustic composer is Alireza Farhang. Farhang, who now lives in France, has collaborated with IRCAM on several occasions and was a co-founder of ACIMC[99] (Association for Iranian Composers of Contemporary Music), which unfortunately ceased its activities in the recent years.

Festival Culture Boom

The activation of access to culture in the late 1990s led to a thaw in the country’s contemporary music scene and prompted more institutions to participate in cultural activities, driven by the new generation of passionate contemporary musicians. The improvement of living conditions and the financial prosperity of Iranian society led more and more private institutions and sponsors to be interested in organising cultural events of great international importance that met the subjective tastes and preferences of their donors. It should be noted, however, that none of these institutions had any connection with the Iranian government, as the field of contemporary art was and still is an undesirable and pro-Western instrument for external propaganda. The only thing that the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance requires from the new organisers is a permit to start their activities, the obtaining of which is a lottery game, depending on the ever-changing political atmosphere at the international and national level. These independent grassroots initiatives are also the reason why collecting history on the development of contemporary and electroacoustic music over the last three decades has become an incredibly difficult puzzle full of gaps and scattered information.

The decade of the 2000s saw the establishment of several contemporary music centres that made outstanding contributions to the development of the arts in Iran. One of the best examples of these efforts is the establishment of the Yarava Music Group[100] with its leader, composer and performer Mehdi Jalali (b.1980). Founded in 1999, the group’s main goal was to introduce Iranians to other, lesser-known types of music than those existing in the country and to create a community for Iranians interested in contemporary music by offering courses, workshops, meeting places and opportunities for learning and knowledge exchange. Among the many activities of the Yarava Music Group are numerous concert series, the establishment of the Yarava Modern Orchestra in 2004, the start of international workshops with invited guest artists from Europe, and the launch of the Electroacoustic Music Composition Competition “Reza Korourian Awards” together with the Tehran International Electronic Music Festival (TIEMF) in 2016[101]. The activities of the Yarava Music Group brought together many Iranian composers associated with the field of electroacoustic music, including one of its pioneers, the composer Shahrokh Khajenouri[102], who still lives in Iran and works with this organisation. Arsalan Abedian (b. 1984), a successful electroacoustic composer who lives in Hanover, also has close professional ties with the Yarava Music Group.

Another long-term initiative for the development of contemporary art in Iran came about thanks to the activities of the artist and curator Amirali Ghasemi (b. 1980). Together with a group of art student friends, Ghasemi founded Parkingallery Projects[103], an independent platform and project space for intermedia art, in 1998. Parkingallery Projects founded the Limited Access International Festival[104], dedicated to presenting events from the new media art scene, spanning moving images, sounds and performance art. The first edition of the festival took place in 2007, and the 9th edition, scheduled for November 2022, has been postponed until further notice. The New Media Society[105], an institution founded in 2014 by Ghasemi, Azadeh Behkish and Bahar Ahmadifar, is a project space, archive and library that documents the activities of the new media scene in Iran. Its focus is mainly on visual arts, although several initiatives have been taken to rediscover electronic music through special concerts and workshops, such as the live coding workshop by composer Sohrab Motabar (b. 1984) or the Microseries concerts in duo with composer Saba Alizadeh (b. 1983). The TADAEX Festival[106], which focused on the world of new media, digital art, computer science, video art and programming, was an annual event that has gathered numerous international visitors in Tehran since 2011. Electroacoustic music performances and audiovisual projects were an integral part of the festival programme. However, the last known edition of the event took place in 2018. After that, the festival finally ceased its activities, most likely due to the increasing economic problems[107] related to the recession and the devaluation[108] of the Iranian currency from mid-2018 and beyond[109].

Sote – Majestic Noise Made in Beautiful Rotten Iran

The radical growth of the underground electronic music scene and the Iranian artists involved in its development can hardly be counted. Deep House Tehran[110] was founded in 2014 under the leadership of charismatic Tehran-based DJ, music producer, composer, sound artist and musician Nesa Azadikhah[111] (b. 1984). It is an online resource website dedicated to building the community of Iranian electronic artists: producing music podcasts and DJ sets, and presenting music reviews, interviews and news about electronic devices. Almost at the same time, in 2015, the artist-run festival SET[112] was launched, thanks to another leading artist in the electronic music scene, Ata Ebtekar aka Sote (b. 1972 in Germany). This electronic composer, sound artist and sound engineer focuses particularly on the use of modern Persian scales, playing with tradition, just as Alireza Mashayekhi did in his electroacoustic works. Following a period of prosperity and greater social freedoms, due in part to the lifting of economic sanctions imposed on Iran by the US and the international community[113], the country’s cultural scene continues to flourish. The Spectro Centre for New Music was founded in 2015 by Iranian composer Idin Samimi Mofakham and Polish composer and conductor Martyna Kosecka to organise workshops, lectures and concerts to promote contemporary music in Iran. In 2016, it joined the International Confederation of Electroacoustic Music CIME/ICEM[114] and actively supported the promotion of Iranian electronic music at the organisation’s international concerts. The latest institution to promote electronic music, the Contemporary Music Circle[115], was founded in 2015 at the Tehran Contemporary Arts Museum. The CMC, led by conductor Navid Gohari, seeks to include music from the contemporary scene in events that can be presented in and connected to the museum’s spaces, but not only. The founding of the CMC and the combined efforts of the Spectro Centre formed the basis for the Tehran International Contemporary Music Festival[116], which has become the only international festival of contemporary music in the Middle East in recent years. Unfortunately, TCMF is currently waiting for a better economic and socio-political atmosphere to resume its activities, like most other organisations based in Iran.

Iranian Women in Electroacoustic Music

In the last two decades, the presence of Iranian women in the global electroacoustic music scene has increased. The male-dominated Iranian society hardly allowed women in various hierarchical structures, not even in the arts, especially in music. The number of female composers in 20th century Iran fluctuated around a few, mostly overshadowed by their male colleagues. This situation is beginning to change drastically at the beginning of the 21st century. Many young Iranian women emigrate from the country and take up music studies in Europe or the USA. Some succeed in travelling abroad to study music, others join the Iranian underground music scene. The most prominent example of the latter practise is perhaps the story of the aforementioned Nesa Azadikhah, who single-handedly built a significant IDM scene in Iran. The sweet promise of the internet, with platforms like Soundcloud, Bandcamp and the vast possibilities of social media, enabled many to release their music independently and quickly. Accessibility to electronic equipment and DAWs like Ableton or Reaper simplified the production process, which was especially handy for electronic music artists. As recently as 2016, Fari Bradley wrote for The Wire that “it’s hard to find a woman making electronic music in Iran, although it is not expressly forbidden.”[117] However, besides DJ Nesa, many other female artists were already active and visible at the time, such as composer and singer Sara Bigdeli Shamloo aka SarrSew (b. 1991), who now lives in Paris. As a member of the experimental ensemble 9T Antiope, which she founded together with Nima Aghiani, SarrSew was also one of the first female electronic artists to be associated with the SET Festival[118]. Iranian-Dutch singer-songwriter Sevdaliza (b. 1987) has been storming the electronic, alternative and experimental pop scene since 2013. Although she moved to the Netherlands with her family at the age of five[119], she also sings in Persian and her art remains closely connected to the history and social reactions to the situation in her home country[120]. Born in Algeria and raised in Tehran, conductor Yalda Zamani (b. 1985), who currently lives in Germany, is a fantastic example of a versatile artist rooted in interdisciplinary practises. As part of the co-funded community WE:Shape[121], she actively promotes diversity in the European contemporary music scene.[122] Furthermore, her work in the field of electronic music revolves around live coding and the application of new technologies in musical performances. A project with the sound artist Hadi Bastani, presented at the KLANGTEPPICH Festival in Berlin in 2021, deserves special mention.[123]

Zamani’s colleague and another co-founder of WE:Shape, the sound artist Rojin Sharafi ( b. 1995), is probably one of the most successful Iranian women artists in the electronic music scene. A strong proponent of interdisciplinary aesthetic thinking[124], Sharifi’s diverse musical practise takes her music into uncharted waters:

“I’m very interested in work that engages different senses, interacts with the audience, changes strategies, and is not very predictable.”[125]

The same can be said about the British-Iranian composer and turntablist Shiva Feshareki ( b. 1987). Feshareki’s music is a mixture of academic composition training, experimental music practises and electronic dance music[126], and cannot be pigeonholed into the existing categories. This phenomenon is a characteristic feature of many Iranian artists in the electronic and experimental scene. Berlin-based Nazanin Noori (b. 1991) describes herself as an “ambient hardcore” artist, although her works are also inspired by the Sufi tradition[127]. A similar aesthetic can be found in another Berlin-based artist, Mentrix, who is also inspired by Sufism. This very mysterious[128] artist fuses Eastern and Western sounds in a way that makes her music simultaneously mesmerising and difficult to understand.

Iranian female artists form a vibrant and important part of the international electroacoustic, electronic and experimental music scene, and the numerous activities, new sound productions and projects are hard to count. However, organisations such as the Iranian Female Composers Association (IFCA)[129], the initiatives mentioned in the previous section of this text and many international platforms and events dedicated to popularising the music of Iranian women artists help to maintain their visibility and prove that Iran’s music scene is diverse, rich and constantly growing.

Rojin Sharifi

Reviving Revolutions

In an interview given to the Ableton platform in 2018, Sote spoke of the role of internet as a tool for communication between Iranian artists and the world:

“I would love to have a weekly show on Iranian radio to introduce the wonderful international phenomena of experimental electronic music to the whole country, but it’s nearly impossible to do such thing when all radio stations and TV stations are government owned and controlled according to a certain taste. So for now, in order to be heard, we have to rely on the internet.”[130]

Who would have thought that his words would become more topical than ever in view of the current political situation in Iran. Once again, Iranian art is at a crossroads. The protests following the untimely death of a young woman, Mahsa Jina Amini, at the hands of the morality police in the capital Tehran[131], which have erupted since 13 September 2022, have grown into a revolution[132] demanding a change of government power and a fight for freedoms and democracy in the country. The story of the development of the contemporary, electronic and electro-acoustic scene in Iran presented in this text is interrupted by another revolution. Arts organisations, festivals and all bilateral cultural initiatives are cancelling or postponing their programmes to focus on how to survive in the shadow of the repressive regime’s struggles or to support the demonstrators on the streets. Many artists, including musicians[133], are imprisoned for their art, their songs, their words and even their actions, while many more risk their lives for freedom and a future without oppression. The revolutionary art of resistance from all genres, coming from all over the world, soothes the sore hearts of Iranians with the promise of a better future.

The Iranian Revolution “Zan, Zendegi, Azadi” of 2022 began with a woman. It is not for nothing that this text ends with the presentation of art by Iranian women artists who belong to the electronic music scene. It shows their presence, importance and perseverance in the art field, proving that curiosity, determination and the need for progress cannot be stopped by anyone. The Iranian contemporary music and dance music scene as it has developed since the 1960s until today shows the diversity of musical inventions and thoughts, but most importantly the ability to build bridges through collaboration and mutual support over the years. In 2023, there is more at stake here than just the future of a particular musical genre or the possibility of free development of the country’s culture. The current battle is about the “to be or not to be” of the nation and its heritage. We can only hope that the sounds of tomorrow will never be silenced.

ENDNOTE LIST

- Nettl Bruno, “IRAN xi. MUSIC,” Encyclopædia Iranica, XIII/5, pp. 474-480, available online at http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/iran-xi-persian-music (accessed on 30 December 2012). ↑

- Refer to Samimi Mofakham, Idin, From Dar Ol-Funun to Tehran Contemporary Music Festival, Glissando Iran 2023, internet edition. ↑

- An interesting read in this subject may be found in Foran John, Fragile Resistance: Social Transformation in Iran from 1500 to the Revolution – A History, Westview Press 1992. ↑

- Cont Arshia, Gluck Bob, Electronic Music in Iran, eContact! 11.4, Toronto Electroacoustic Symposium 2009, Canadian Electroacoustic Community. ↑

- Farhang Alireza, Electronic Music in Iran: Tradition and Modernity, Université Paris-Sorbonne Paris-IV, 2009, p.2. ↑

- More information on Reza Shah can be found at https://www.britannica.com/biography/Reza-Shah-Pahlavi ↑

- Church Michael, The Other Classical Musics: fifteen great traditions, Aga Khan Trust for Culture Music Initiative, The Boydell Press 2015, p. 327-328. ↑

- On Industrialization of Iran; go to http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/industrialization-i ↑

- Cont Arshia, Gluck Bob, Electronic Music in Iran, eContact! 11.4, Toronto Electroacoustic Symposium 2009, Canadian Electroacoustic Community. ↑

- Gluck Bob, A New East-West Synthesis, Conversations with Iranian Composer Alireza Mashayekhi, eContact! 14.4, – TES 2011: Toronto Electroacoustic Symposium. ↑

- Ibidem. ↑

- According to Mashayekhi’s memories in https://vista.ir/m/a/14j9h (entry in Farsi) accessed – 3.02.2020. ↑

- Gluck Bob, A New East-West Synthesis, Conversations with Iranian Composer Alireza Mashayekhi, eContact! 14.4, – TES 2011: Toronto Electroacoustic Symposium. ↑

- Cont Arshia, Gluck Bob, Electronic Music in Iran, eContact! 11.4, Toronto Electroacoustic Symposium 2009, Canadian Electroacoustic Community. The electronic studio of The University of Utrecht will take the name of the Sonology Institute from 1967. ↑

- Based on Mashayekhi’s memories presented at Gluck Bob, A New East-West Synthesis, Conversations with Iranian Composer Alireza Mashayekhi, eContact! 14.4, – TES 2011: Toronto Electroacoustic Symposium. ↑

- Cont Arshia, Gluck Bob, Electronic Music in Iran, eContact! 11.4, Toronto Electroacoustic Symposium 2009, Canadian Electroacoustic Community. ↑

- The information about Mashayekhi’s first electronic works from 1965 is specifically used by Gluck Cont in the work Electronic Music in Iran. Mashayekhi himself, in the conversation with Bob Gluck, speaks of the period 1965-1968 as the time of his first electronic works. However, there is no precise information about the composer’s electronic attempts from this period, apart from the completed composition Shur published in the official list of composer’s works [auth.]. ↑

- Some sources state the completion of “Shur” for 1966, i.e. in the master thesis of Alireza Ostovar: “Trascultural Music: A research about Intercultural and Transcultural Processes in electroacoustic music, conducted at Folkwang Universitat der Kunste in September 2018, p.27. However, the bulk of sources state the date of 1968 as the date of completion of the work [auth.]. ↑

- Exact list of compositions published on Electronic Panorama Philips can be found here: https://www.discogs.com/Various-Electronic-Panorama-Paris-Tokyo-Utrecht-Warszawa/release/328100, accessed on 3.01.2020. ↑

- The word used by composer to describe a research in music, in Gluck Bob, A New East-West Synthesis, Conversations with Iranian Composer Alireza Mashayekhi, eContact! 14.4, – TES 2011: Toronto Electroacoustic Symposium. ↑

- Information taken from CD compilation booklet “Alireza Mashayekhi – Happy Electronic Sounds”, published by Musical Center of Hozeh Honari in 2005, material in Farsi, booklet, p. 7. ↑

- Cont Arshia, Gluck Bob, Electronic Music in Iran, eContact! 11.4, Toronto Electroacoustic Symposium 2009, Canadian Electroacoustic Community. ↑

- Gluck Bob, A New East-West Synthesis, Conversations with Iranian Composer Alireza Mashayekhi, eContact! 14.4, – TES 2011: Toronto Electroacoustic Symposium. ↑

- Gluck Bob, A New East-West Synthesis, Conversations with Iranian Composer Alireza Mashayekhi, eContact! 14.4, – TES 2011: Toronto Electroacoustic Symposium. ↑

- According to the catalogue of compositions provided by the composer’s assistant, 46 works combined electronic component until 2019 [auth.]. ↑

- In the official transcriptions of Persian names and surnames from Farsi into English, translation efforts often find many inaccuracies and alternative spellings. This is also the case with this composer’s surname. In my research paper, I use the translation “Dolatshahi” used on the composer’s official website, but the quotations I refer to in the footnotes are spelled as they were written by the original author of the research reference. It is important to add that in a full research on the composer, both in books and in internet sources, alternative spellings of Dolatshahi are found, such as: “Dolat-shahi”, “Dolat Shahi” or “Dolat-Shahi” [auth.]. ↑

- Gluck Bob, An Eclectic Iranian-American Composer and Artist, Conversation with Dariush Dolat-shahi, eContact! 15.2, Toronto Electroacoustic Symposium 2012. ↑

- From the Wikipedia entry on Dariush Dolatshahi, https://bit.ly/3gZHQKx (entry in Farsi), accessed on 15.01.2020. ↑

- Gluck Bob, An Eclectic Iranian-American Composer and Artist, Conversation with Dariush Dolat-shahi, eContact! 15.2, Toronto Electroacoustic Symposium 2012. ↑

- Ibidem. ↑

- Gluck J. Robert, The Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center: Educating International Composers, Computer Music Journal, Vol. 31, No. 2, Creating Sonic Spaces (Summer, 2007), The MIT Press, p.26. ↑

- Gluck Bob, An Eclectic Iranian-American Composer and Artist, Conversation with Dariush Dolat-shahi, eContact! 15.2, Toronto Electroacoustic Symposium 2012. ↑

- Ibidem. ↑

- Gluck Bob, An Eclectic Iranian-American Composer and Artist, Conversation with Dariush Dolat-shahi, eContact! 15.2, Toronto Electroacoustic Symposium 2012. ↑

- Cont Arshia, Gluck Bob, Electronic Music in Iran, eContact! 11.4, Toronto Electroacoustic Symposium 2009, Canadian Electroacoustic Community. ↑

- Gluck Bob, An Eclectic Iranian-American Composer and Artist, Conversation with Dariush Dolat-shahi, eContact! 15.2, Toronto Electroacoustic Symposium 2012. ↑

- Ibidem. ↑

- Ibdem. ↑

- Ibidem. ↑

- From composer’s brief biography in Wikipedia Farsi, https://bit.ly/38VXPqe, accessed 4.05.2020. ↑

- Ibidem. The name of Khajenouri’s electronic music teacher is often misspelled in Farsi translations. For the correct information about Michael Graubart, Austrian composer who fled to England, read here: http://www.mvdaily.com/articles/g/m/michael-graubart.htm, accessed 4.05.2020. ↑

- Cont Arshia, Gluck Bob, Electronic Music in Iran, eContact! 11.4, Toronto Electroacoustic Symposium 2009, Canadian Electroacoustic Community. ↑

- Ibidem. ↑

- Gluck J. Robert, The Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center: Educating International Composers, Computer Music Journal, Vol. 31, No. 2, Creating Sonic Spaces (Summer, 2007), The MIT Press, p.23. ↑

- Information from the movie series on Ahmad Pejman (in Farsi) by Hossein Salamat for www.artebox.ir, link to the compilation online https://bit.ly/3j82cmI, accessed on 5.06.2020. ↑

- Gluck J. Robert, The Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center: Educating International Composers, Computer Music Journal, Vol. 31, No. 2, Creating Sonic Spaces (Summer, 2007), The MIT Press, p.26. ↑

- Hormoz Farhat, “SHIRAZ ARTS FESTIVAL,” Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition, 2015, available at http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/shiraz-arts-festival (accessed on 02 December 2015). ↑

- Gluck J. Robert, The Shiraz Festival: avant-garde arts performance in 1970s Iran, p.216. ↑

- Ibidem. ↑

- Mahlouji Vali, The Super-Modernism of the Festival of Arts, Shiraz-Persepolis, di’van: a journal of accounts, issue 2, july 2017 p.44. ↑

- Gluck J. Robert, The Shiraz Festival: avant-garde arts performance in 1970s Iran, p.216.

It is important to add that the two sources mentioned above present the theme of festival leadership in a slightly different form. The author of this paper assumes that the creation of the artistic content of the festival was in fact a joint effort of Reza Ghotbi and Sheherazade Afshar Ghotbi and the other advisors, such as Bijan Saffari, Hormoz Farhat or Fozié Majd. ↑ - Gluck J. Robert, The Shiraz Festival: avant-garde arts performance in 1970s Iran, p.216. ↑

- Gluck J. Robert, The Shiraz Festival: avant-garde arts performance in 1970s Iran, p.217. ↑

- Solomos Makis, Xenakis first composition in musique concrete: Diamorphoses, Xenakis International Symposium, CCMC, Goldsmiths, University of London Southbank Centre, 1-3 April 2011, symposium materials. ↑

- Harley James, The Electroacoustic Music of Iannis Xenakis, Computer Music Journal, Vol. 26, No. 1, The MIT Press, In Memoriam Iannis Xenakis (Spring, 2002), p. 45. ↑

- Ibidem, p.45-46. ↑

- Gluck J. Robert, The Shiraz Festival: avant-garde arts performance in 1970s Iran, p.217. ↑

- To compare and draw your own conclusions, look into the Catalouge of works performed at Shiraz Arts Festival by Sheherazade Afshar Ghotbi [auth.]. ↑

- Farhang Alireza, Electronic Music in Iran: Tradition and Modernity, Université Paris-Sorbonne Paris-IV, 2009, p.2. ↑

- Permanent is performed on 17.08.1974 by the National Iranian Radio & Television Chamber Orchestra conducted by Diego Masson and repeated on 26.08.1977 by the same ensemble but conducted by Maurice Le Roux. The composition Contradictions is performed by the American Brass Quintet on 27.08.1976. ↑

- Cont Arshia, Gluck Bob, Electronic Music in Iran, eContact! 11.4, Toronto Electroacoustic Symposium 2009, Canadian Electroacoustic Community. ↑

- The composition Two Movements for String Orchestra is premiered on 27.08.1971 by the National Iranian Radio & Television Chamber Orchestra conducted by Farhad Meshkat, and the work May 1973 is premiered on 7.09.1973 by the same orchestra but conducted by Catherine Comet. ↑

- Gluck J. Robert, The Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center: Educating International Composers, Computer Music Journal, Vol. 31, No. 2, Creating Sonic Spaces (Summer, 2007), The MIT Press, p.31. ↑

- Gluck J. Robert, The Shiraz Festival: avant-garde arts performance in 1970s Iran, p.219. ↑

- Robert Gluck, in another essay on the Shiraz Arts Festival, quotes a review of Mirage from the Tehran Journal (25.06.1977) which, according to critic Shaghaghi, “easily unfolded its beauty; it bloomed as fast as it was started, the sound effects and the orchestral music blended harmoniously”. Robert Gluck, The Shiraz Arts Festival, Western Avant-Garde Arts in 1870s Iran, Leonardo 2007, Vol. 40, No 1, p.24. ↑

- According to footnote [30] on the correct spelling of Dariush Dolatshahi’s surname, this also applies to the name Fozié Majd. In this text, I present the version used by the composer herself as the correct one, but it is important to point out that one can find these alternative spellings when doing research: Fouzieh, Fozieh, Fawzieh, Fuzie or Fuzieh. ↑

- Mahasti Afshar, Festival of Arts Shiraz-Persepolis, Asia Society, symposium on The Shiraz Festival, New York, 5.10.2013, p.5. ↑

- The NIRT Chamber Orchestra conducted by Catherine Comet premieres Shabkuk for string orchestra on 5 September 1973 and Hell is but a sparkle of our futile suffering is premiered on 21 August 1976 by the same ensemble but conducted by Ivo Malec. Fozié Majd’s film music can be heard in Siavash in Persepolis by Fereydun Rahnema, shown at the Shiraz Arts Festival in 1967, and in The Son of Iran is without news of his mother by Fereydun Rahnema, shown at the Shiraz Arts Festival in 1976. ↑

- Mahasti Afshar, Festival of Arts Shiraz-Persepolis, Asia Society, symposium on The Shiraz Festival, New York, 5.10.2013, p.27-28. ↑

- Fozié Majd is famous for her contribution to ethnomusicology in Iran. She is the founder and director of the NIRT Center for the Collection and Study of Regional Music since its establishment in 1973 [auth.]. ↑

- From the booklet of 2nd Tehran International Electronic Music Festival of 1-8 September 2018, where Fozié Majd’s Songs of Separation were performed. ↑

- From the fragment of Iannis Xenakis’s letter to the organizers of Shiraz Arts Festival and its artistic head, Farrokh Ghaffari, found in Gluck J. Robert, The Shiraz Festival: avant-garde arts performance in 1970s Iran, p.220. ↑

- Detailed information on the reasons for and the development of the 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran is analysed extensively in a large number of publications. Probably the most compact information can be found in the Encyclopaedia Iranica in the Iran section. Iranian History (2) Islamic Period under the link www.iranicaonline.org/articles/iran-ii2-islamic-period-page-6. ↑

- Mahasti Afshar, Festival of Arts Shiraz-Persepolis, Asia Society, symposium on The Shiraz Festival, New York, 5.10.2013, p.41. ↑

- To read more about the Islamic Revolution, follow the link in endnote [78]. ↑

- Gluck J. Robert, The Shiraz Festival: avant-garde arts performance in 1970s Iran, p.220. ↑

- Gluck Bob, An Eclectic Iranian-American Composer and Artist, Conversation with Dariush Dolat-shahi, eContact! 15.2, Toronto Electroacoustic Symposium 2012. ↑

- For an interesting read on the last years of Pahlavi rule and their flight from Iran, see Cooper Andrew Scott, The Fall of Heaven: The Pahlavis and the Final Days of Imperial Iran, published in 2016 by Henry Holt and Co. ↑

- An interesting publication on the life of Khomeini and the 1979 events can be found in Moin Baqer, Khomeini: Life of the Ayatollah, published by St Martin’s Press on 2000. ↑

- Kiftner, John, Khomeini Bans Broadcast Music, Saying It Corrupts Iranian Youth, New York Times, July 24, 1979 Section A, Page 1, https://www.nytimes.com/1979/07/24/archives/khomeini-bans-broadcast-music-saying-it-corrupts-iranian-youth.html, accessed on 8.01.2023. ↑

- Ibidem. ↑

- Jakubiak, Karolina, Nagraj mi rewolucję. Rola kaset magnetofonowych w przygotowaniach do irańskiej rewolucji islamskiej, Glissando 2.10.2020, https://glissando.pl/artykuly/nagraj-mi-rewolucje-rola-kaset-magnetofonowych-w-przygotowaniach-do-iranskiej-rewolucji-islamskiej/, accessed on 5.12.2022. ↑

- Warwick, Oli, Sote is helping Iran’s experimental electronic music scene become a powerful cultural force, factmag.com, 3 September 2017, https://www.factmag.com/2017/09/03/sote-iran-ata-ebtekar-interview/, accessed on 15.12.2022. ↑

- Askew, Joshua, What happened when Iran criminalised music after the 1979 Islamic Revolution?, euronews.culture, 26.05.2022, https://www.euronews.com/culture/2022/05/26/what-happens-when-a-country-criminalises-music, accessed on 7.12.2022 ↑

- Gluck Bob, An Eclectic Iranian-American Composer and Artist, Conversation with Dariush Dolat-shahi, eContact! 15.2, Toronto Electroacoustic Symposium 2012. ↑

- The label Folkways Records became the part of the Smithsonian in 1987. For the full catalogue and information visit: https://folkways.si.edu/folkways-records/smithsonian [auth.] ↑

- The only preceding preserved composition is Alireza Mashayekhi’s Back to Tonbak op.67 for Tonbak and computer generated sounds from 1979 [auth.]. ↑

- From the booklet description to the vinyl publication of Electronic Music, Tar and Setar, written by Rachel S. Siegel. ↑

- Gluck Bob, An Eclectic Iranian-American Composer and Artist, Conversation with Dariush Dolat-shahi, eContact! 15.2, Toronto Electroacoustic Symposium 2012. ↑

- From the booklet description to the vinyl publication of Otashgah. Electronic Music by Dariush Dolat-shahi. “Place of Fire” by Perry Goldstein. ↑

- Semati, Mehdi, Media, Culture and Society in Iran: Living with Globalization and the Islamic State,.London, New York: Routledge, 2008. ↑

- Maghazei, Malihe, Trends in Contemporary Conscious Music in Iran, LSE Middle East Centre Paper Series / 03 June 2014. ↑

- Farhang Alireza, Electronic Music in Iran: Tradition and Modernity, Université Paris-Sorbonne Paris-IV, 2009. ↑

- Cont Arshia, Gluck Bob, Electronic Music in Iran, eContact! 11.4, Toronto Electroacoustic Symposium 2009, Canadian Electroacoustic Community. ↑

- Abedian, Arsalan, Leben im Verborgenen. Neue Musik im Iran, Musik Texte 143, Verlag MusikTexte; Köln, November 2014, s.21. ↑

- For further research and detailed information on the beginnings of the experimental music scene in Iran, it is worth reading Hadi Bastani’s dissertation Recent Experimental Electronic Music Practices in Iran: an Ethnographic and Sound-based Investigation, developed at the Sonic Arts Research Centre at Queen’s University Belfast in 2019. Link to the thesis: https://www.hadibastani.com/phd-thesis ↑

- Cont Arshia, Gluck Bob, Electronic Music in Iran, eContact! 11.4, Toronto Electroacoustic Symposium 2009, Canadian Electroacoustic Community. ↑

- Wikipedia entry on the composer in Farsi, shorturl.at/knFT2, accessed on 14.12.2022. ↑

- Although the association is no longer active, the website is accessible with valuable information: https://a-c-i-m-c.org [auth.] ↑

- Detailed information about the group activity can be found on their website (only in Persian) – https://www.yarava.com/ [auth.]. ↑

- Information about the most recent Festival edition can be accessed here: https://www.concertzender.nl/tiemf-iran-electronic-frequencies/ [auth.]. ↑

- Refer back to the short information in the section Dariush Dolatshahi and Iranian Electroacoustic Composers in 1970s [auth.]. ↑

- http://archive.parkingallery.org/about/, accessed on 15.12.2022. ↑

- https://newmediasoc.com/limited-access/, accessed on 15.12.2022. ↑

- https://newmediasoc.com/new-media/about/, accessed on 15.12.2022. ↑

- The last known information about The 8th edition of TADAEX, https://darz.art/en/artfairs/tadaex/57, accessed on 20.12.2022. ↑

- I recommend reading the Wikipedia entry that describes in great detail the development of the 2018-2019 protests in the context of the economic crisis in Iran. It can be accessed here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2018%E2%80%932019_Iranian_general_strikes_and_protests [auth.]. ↑

- Turak, Natasha, Iran’s currency crisis could bring it one step closer to economic collapse, cnbc.com, April 12, 2018, https://www.cnbc.com/2018/04/12/irans-currency-crisis-brings-it-one-step-closer-to-economic-collapse.html, accessed on 29.12.2022. ↑

- Author unknown, Iran’s currency plunges to record low as US sanctions loom, Aljazeera, News Agencies, 29 July 2018 https://www.aljazeera.com/economy/2018/7/29/irans-currency-plunges-to-record-low-as-us-sanctions-loom, accessed on 29.12.2022. ↑

- http://deephousetehran.net/about/, accessed on 6.12.2022. ↑

- To read the story of DJ Nesa and the establishment of Deep House Tehran, visit here: https://www.electronicbeats.net/dj-nesa-iran/ [auth.]. ↑

- https://setfest.org/about/, accessed on 6.12.2022. ↑

- Meignan, William, Iran: Two Years After the Lifting of International Sanctions, globaleurope.eu, 16 January 2018, https://globaleurope.eu/globalization/iran-two-years-after-the-lifting-of-international-sanctions/, accessed on 13.12.2022. ↑

- http://spectrocentre.com/spectro-centre-new-music-member-cime/, accessed on 19.12.2022. ↑

- https://www.facebook.com/cmc.tmoca, accessed on 13.12.2022. ↑

- https://tehrancmf.com/fa-ir/, accessed on 13.12.2022. ↑

- Bradley, Fari, A new generation of electronic musicians in Tehran are using gallery spaces and online networks to connect at home and overseas, The Wire, October 2016 (Issue 392), p.20. ↑

- Faber, Tom, Hardcore sounds from Tehran, RA Magazine, 6 December 2018, https://ra.co/features/3370, accessed on 5.01.2023. ↑

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sevdaliza, accessed on 30.12.2022. ↑

- Listen to the newest song composed in response to the “Women, Life, Freedom” movement and published on 7th October 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M1v37uV6vik [auth]. ↑

- https://www.weshape.network/, accessed on 10.12.2022. ↑

- https://www.yaldazamani.com/about, accessed on 10.12.2022. ↑

- More information about the project and the video from the performance available here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bQv_F7jfBqw ↑

- https://rojinsharafi.com/present-past-future/, accessed on 5.01.2023. ↑

- Shuttleworth, Alastair, ‘It will rock your house!’ Inside the Iranian electronic underground, The Gaurdian, 25 March 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/music/2019/mar/25/inside-the-iranian-electronic-underground-ata-ebtekar-set-festival-mahdyar, accessed on 5.01.2023. ↑

- https://studiofeshareki.com/about, accessed on 5.01.2023. ↑

- Refer to the project Haal, https://www.hoerspielundfeature.de/haal-100.html, accessed on 4.01.2023. ↑

- There is no biography of the artist that can be traced in the internet, and the existing information is very limited. Visit the artist’s Bandcamp profile: https://mentrix.bandcamp.com/ [auth.]. ↑

- For more information, enter here: https://niloufarnourbakhsh.com/ifca/ ↑

- Author unknown, Sote: Radical Electronics from Iran, Ableton.com, 9 March 2018, https://www.ableton.com/en/blog/sote-electronic-music-iran/, accessed on 1.12.2022. ↑

- McGrath, Maggie, Mahsa Amini: The Spark That Ignited A Women-Led Revolution, Forbes.com, 6 December 2022, https://www.forbes.com/sites/maggiemcgrath/2022/12/06/mahsa-amini-the-spark-that-ignited-a-women-led-revolution/?sh=76eed705c3db, accessed on 5.01.2023. ↑

- Perelman, Marc, ‘This Iranian revolution cannot be silenced,’ says activist Hamed Esmaeilion, france24.com, 4 January 2023, https://www.france24.com/en/tv-shows/the-interview/20230104-ani, accessed on 7.01.2023. ↑

- https://iranwire.com/en/politics/108113-popular-protest-singer-shervin-hajipour-arrested/, accessed on 10.01.2023. ↑