From Dar Ol-Funun to Tehran Contemporary Music Festival

Whenever I have participated in a music festival in recent years (as a performer, composer and lecturer or simply as a visitor) and the conversation turned to Iranian music, the first question I was asked was: “What is the state of contemporary music in Iran? What is the new music scene in Iran and how big is the community of listeners of this music?” My answer has always been, “It’s a bit complicated!”

As you can imagine, the music scene in Iran today is quite big and diverse. Different initiatives in Iran focus on different genres of music, from traditional Iranian music shows to extremely loud, experimental underground concerts. In order to get a better overview and understanding of contemporary music in Iran, as a general term rather than a specific genre of music, we need to take a little time travel through Iranian music history. We will look at the history of the development of music education and find some critical moments in the history of Iranian composers and the Iranian school of composition, which is very young and growing very fast.

Classical (Western traditional) music is still very young in Iran. As in most non-European countries, it was brought here by European musicians. They were invited to Iran by the country’s rulers or by the Eurocentric Iranian reformers who believed in Westernisation. They studied abroad, mainly in Central Europe, and then returned to Iran. Since the first days of the presence of Western music in Iran, music theorists and musicians have begun to use the words “musiqi-ye kelāsik”, which refers to “Western classical music”, and “musiqi-ye dastgāhi”, which stands for “Iranian classical music”. This article is about describing the beginnings and emergence of “musiqi-ye kelāsik” and how this particular genre developed in my home country, Iran.

History of music education and western music in Iran

Iran’s first faithful reformer and Prime Minister Amir Kabir (1807 -1852) founded Dar Ol-Funun, the first modern university and university in Iran, in 1851, a year before his dismissal and execution. The aim of Dar Ol-Funun was to educate upper-class Persian youth in medicine, engineering, military science and geology. Later, music and fine arts, especially painting, were also included in the programme of this university (Diba, 2013).

In 1856, several French advisers were settled in Tehran, the capital of Iran, to help and modernise the Iranian army. Among the advisers were two musicians, Bosquet and his deputy Rouyon. They began teaching Western music to the military students of Dar Ol-Funun and preparing them to form a military orchestra for official occasions such as parades and royal celebrations. However, Bosquet and Rouyon were unsuccessful in training the students and failed to convince Nasser-al-Din Shah[1] (1831-1896), who wanted a military orchestra built on the Western model. Bosquet left Iran after two years, and Rouyon was not strong enough to continue work on the military orchestra. Therefore, Nasser-al-Din Shah ordered the hiring of a professional musician to train the students musically and prepare the orchestra he dreamed of. Considering the close relations with the French government, Iran hired the French military musician and composer Alfred Jean-Baptiste Lemaire (1842 -1907) in 1867 (Advielle, 1885).

A former teacher at the Paris Conservatoire, Lemaire established an eight-year music education system in Dar Ol-Funun that mirrored the organisational order of his country’s educational standards. With the help of Mirza Ali-Akbar Khan, who studied painting in France, Lemaire translated the first theory and harmony textbooks from French into Farsi. In the beginning, Lemaire was the only teacher at the music school. He taught the Iranian students all the necessary subjects such as ear training, harmony, counterpoint, piano and all techniques for brass and woodwind instruments. In 1873, Lemaire was commissioned by Nasser-al-Din Shah to compose the King’s Salute as the royal and national anthem of Iran, which was played at official ceremonies and during the King’s European travels between 1873 and 1909.

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/9d/Salam-e_shah_1906.ogg

Recording of The Royal Salute by Alfred Jean-Baptiste Lemaire from 1906.

In 1909, Lemaire died in Tehran after working as a teacher and conductor for forty-two years. After his death, the government decided to stop hiring foreigners, so the music school in Dar Ol-Funun had to be closed.

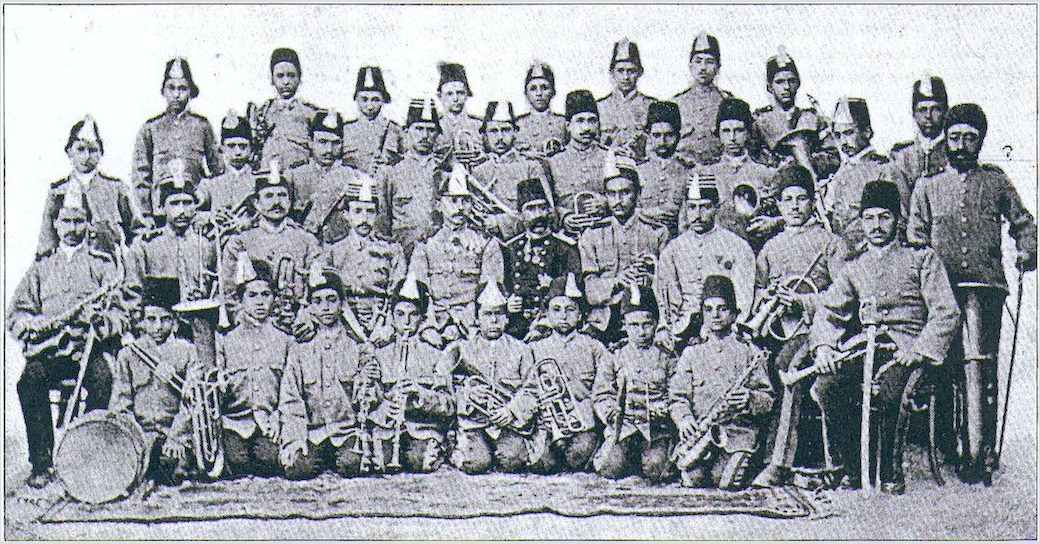

The imperial music orchestra (15 May 1873) – Lemaire is the sixth person from right in the second row

After five years, now under the direction of Qolam-Reza Minbashian, the school was reopened in 1914. Qolam-Reza Minbashian (1861-1935), also known as Salar-e Mo’azzez, was an Iranian composer, military man and the author of the first Iranian National March (1909), which was to replace Lemaire’s Royal Salute. He was one of Lemaire’s first students and continued his musical studies at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory in the class of Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov (Pourghanad, 2018). During the constitutional revolution in Iran (1905 and 1911), he lived in France and upon his return to the country, became the first Iranian musician to be appointed director of the music school in the era of modern music education in Iran (Bastaninezhad, 2014).

Qolam-Reza Minbashian (1861-1935)

Before Minbashian became the school’s headmaster, the only students at the music school were those with military functions. According to the official website of the Tehran Music School, in 1915, when the music school separated from Dar Ol-Funun and was renamed Madrese-ye Mosique (translated from Farsi as “the music school”), the management of the school was systematically transferred from the Ministry of Defence to the Ministry of Education. With these changes, it was already possible for anyone who had attended the sixth-grade education to apply for the conservatoire and, after six years of intensive musical training, receive the music diploma, which at the time was equivalent to a high school diploma. Qolam-Reza Minbashian made it compulsory for all applicants to learn French. As a final exam of the six-year course, students had to compose or orchestrate a piece of music. For those who had a military background, it was compulsory to compose or orchestrate a march, while the others were free to choose. In addition, at the end of their exam, students had to conduct their compositions or orchestrations with the Madrese-ye Musique orchestra. Qolam-Reza Minbashian was one of the first to translate traditional Iranian music into the Western notation system. He translated books on theory, harmony, instrumentation and orchestration from French and his publications served as the main source for teaching at Madrese-ye Musique during his time as director of the music school (Darvishi, 1994).

In 1928, Ali-Naqi Vaziri (1886-1979), a composer, virtuoso tar player, music theorist and pedagogue who had studied music theory and composition in France and Germany, was appointed the new director of the music school. At his suggestion, the name of the school was changed again, this time to Honarestān-e Musiqi (from Farsi: “the music conservatory”). On his orders, all military students were removed from the school and as he believed in education for all members of society, he fought for the right of women to receive music lessons at the music conservatory. Another revolutionary act of Vaziri was to make it compulsory for every student to learn Western and Iranian instruments so that both “musiqi-ye dastgāhi” and “musiqi-ye kelāsik” could be preserved and shape the musical thinking of the students of this institution. Moreover, due to the above-mentioned reform, in addition to learning Western music theory and harmony, everyone had to study Radif, the basic concept of Iranian classical music.

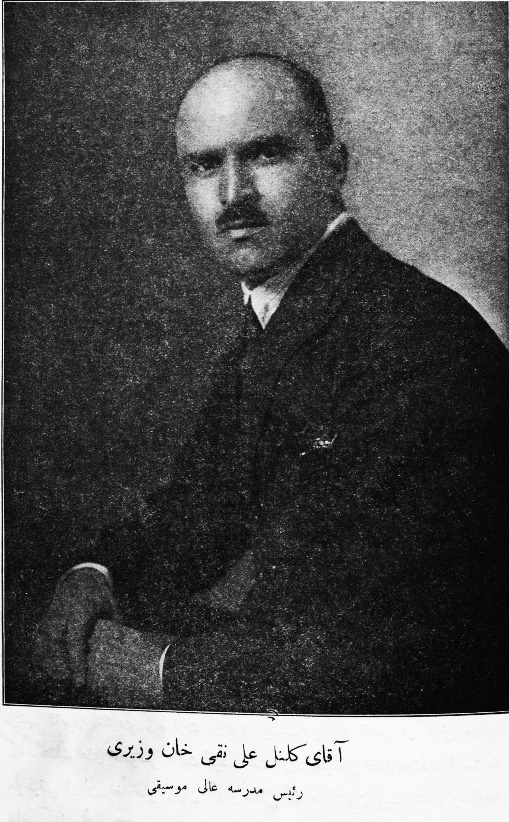

Ali-Naqi Vaziri (1886-1979) – Picture dated at 1925

It is important to add that Vaziri was the first to believe that traditional Iranian music should be theorised and taught on the basis of the Western music pedagogical system. In 1920, he invented sori and koron, two accidentals that are crucial to the notation of Iranian microtones. This was followed by the invention of a 24-quarter-tone scale as the basis for Persian music, created to translate the Radif of Iranian classical music into the Western notation system. Vaziri began notating Radif based on the interpretation of Mirza Abdollah, one of the most important tar and setar players in the history of Iran (Farhat, 2004). He is also the author of the first textbook for teaching the tar in 1922, which focuses on the techniques of tar playing and includes exercises and pieces for the instrument (Farhat, 2003).

Two accidentals used in notation of Iranian microtones, from the left: Sori (1/4 pitch up) and Koron (1/4 pitch down)

Vaziri’s books, especially The Theory of Music (Musiqi-ye Nazari) (1934) and The Quarter-tone Harmony of Iranian Music (1935), are the first attempts to theorise and harmonise traditional Iranian music on the basis of a five-stave system. As a composer, Vaziri wrote numerous compositions for various musical media, from music for Iranian solo instruments to symphonic music and even several operettas in Farsi. His contributions to the development of music theory in Iran are inestimable.

One of the most notable graduates of this period of the Tehran Conservatory of Music was Abolhasan Saba (1902-1957). Saba was a well-known violinist and setar player and composed music based on Iranian folklore and regional music. In 1927, Vaziri commissioned Saba to open a branch of the music conservatory in Rasht, a city in northern Iran. Saba spent two years there, collecting and notating several folk tunes of the region and composing several compositions based on these tunes and modes. Like his teacher Ali-Naqi Vaziri, Saba was one of Iran’s most important educators and trained some of the most influential musicians of the next generation. During his prolific life, he wrote several study books on Iranian-style violin playing, santoor (Iranian plucked instrument), tar and setar course books. His publications on Iranian style violin playing are still the main source for teaching this style in music schools in Iran (Mohebi, 2005).

Idin Samimi Mofakham – Hommage A’ Abolhasan Saba for violin and cello (2012) Based on a folk tuned transcribed by Saba

In 1934, Qolam-Hossein Minbashian (1907-1978), the son of Qolam-Reza Minbashian, became the head of the music conservatory on the orders of Reza Shah, the first king of the Pahlavi dynasty. He studied violin and piano in Dar Ol-Funun, harmony and composition at the Geneva Conservatoire. And later the basics of conducting at the Berlin Academy of Music. Minbashian was a strict and Eurocentric person and did not believe that Iranian classical music was worthy enough to be taught at the conservatoire. In his view, Iranian music had no purpose other than to excite the prurient thoughts of listeners and belonged only to accompany festivities; and it did not deserve to occupy an important place in the arts. With this radical undermining of Iranian music, Minbashian, as director of the Music Conservatory in Tehran, ordered that all theoretical and practical classes of Iranian music be removed from the school. Determined to realise his vision, he invited musicians from Czechoslovakia to teach Western music at the conservatory and to join the Municipality Symphony Orchestra founded in 1933, naturally to perform mainly compositions by European composers and himself (Ḥoseyni Dehkordi, 2005).

In addition to his radical and controversial activities at the conservatoire, Minbashian is credited with founding the music department of the Ministry of Culture in 1938 and co-founding Majalla-ye Musiqi (The Music Journal), the first professional music journal in Iran, in 1939. He also founded school choirs and composed several hymns for them (Khāliqī, 1974/2003).

Municipality Symphony Orchestra – Qolam-Hossein Minbashian as conductor – (year unknown)

Mostafa Kamal Pourtorab (1924-2016) was one of the most distinguished students of the Tehran Conservatory of Music. He started playing the flute at the age of five without having a teacher and eventually entered the music conservatory at the age of fifteen and began playing the bassoon and violin. At the same time, he started learning tar and Iranian music theory in Ruhollah Khaleqi’s class and then music composition in Parviz Mahmoud’s private lessons. Pourtorab began teaching harmony and counterpoint at the conservatory in 1967 and was appointed director of his alma mater from 1971 to 1973. He wrote and translated numerous articles and books in/to Farsi. His book “The Theory of Music” (1966) is still one of the most important sources for music theory.

The political changes in Iran, especially the Anglo-Soviet invasion and occupation of Iran in 1941, had an impact on the arts and especially on the music scene. The new Iranian Prime Minister Mohammad-Ali Foroughi[2] (1877-1942), a nationalist and ardent supporter of traditional Iranian music, removed Qolam-Hossein Minbashian from the post of Music Conservatory and appointed Vaziri as the head of the institution, believing that this measure could save traditional Iranian music from rejection in the music education system and in musical practise. In 1942, the academic year began with the instruction that every student should learn both Iranian and Western instruments and music theory, as had been introduced under Vaziri’s first leadership.

In 1946, the composer and conductor Parviz Mahmoud (1910 – 1996), who had already studied music at the Tehran Conservatory of Music in the days of Qolam-Reza Minbashian and completed composition studies at the Royal Conservatory in Brussels, became the school’s new director. In the same year, he revived the Qolam-Hossein Minbashian Municipality Symphony Orchestra, which had been closed after Minbashian’s ouster in 1942. He changed the name of the orchestra to the Tehran Symphonic Orchestra, which still exists and operates under the same name as a state-supported arts institution.

Tehran Symphonic Orchestra in rehearsal, Morteza Hannaneh (conductor), Tania Ashot (Piano) – (1951-2)

Mahmoud was against teaching Iranian music at the music conservatoire, not because he did not approve of it, but because he believed that it could not be taught systematically. In his opinion, it would be better to teach it according to the old system of oral instruction between master and pupil. In 1948, again, all Iranian instruments and theoretical subjects were dropped from the school’s curriculum, so that only Western music could be learned.

Hossein Nassehi (1925-1977) and Samin Baghtcheban (1925-2008) were two of the most influential Iranian composers who studied at the Music Conservatory in the years mentioned. Later, both became teachers there and introduced their students to many new and challenging concepts in music and composition. Nassehi was a lecturer, composer and trombonist. He studied trombone and soon became a member of Parviz Mahmoud’s Tehran Symphonic Orchestra. In 1944, as part of an educational exchange between Iran and Turkey, he was among the Iranian musicians who received a scholarship to study composition at the State Conservatory of Hacettepe University in Ankara. After his return to Iran in 1949, Nassehi began teaching counterpoint and composition at the music conservatory. Parviz Mansouri (1925-2011), Ahmad Pejman (b. 1935) and Hossein Dehlavi (1927-2019) were among his most important students (Unknown, 2019). Due to his political activities, his music was banned from performance in Iran and most of his scores were lost after his sudden death at a very young age. While this article was being revised in 2023, Mehrdad Gholami, a flautist living in the US, performed his Canta for Flute and Orchestra (1959) in Tehran in July 2022. Interestingly, the handwritten score was found in the archives of the Tehran Symphony Orchestra.

Parviz Mansouri began playing the violin at a very young age, but his serious musical training did not begin until he was admitted to the violin class at the Tehran Conservatory of Music in 1948. He began studying music theory in the class of Hossein Nassehi and then moved to Austria to continue his studies in music theory and composition in the class of Hanns Jelinek. In 1970 he returned to Iran, but due to his political views and activities he never had a chance to get a job at the music conservatory. He left Iran in the early 1980s and settled in Vienna until his death. Among his writings, his book The Fundamentals of Music Theory (1991) is another important source for the next generations of music students in Iran (Khoshnam, 2011).

Ahmad Pejman is a composer of several operas and ballets. He began his musical education in high school in the private classes of Heshmat Sanjari (violin) and Hossein Nassehi (music theory). With a scholarship, he then continued his composition studies at the Music Academy in Vienna in the classes of Thomas Christian David, Alfred Uhl, Hanns Jelinek and Friedrich Cerha. In 1967, while still studying at the Vienna Music Academy, he composed his first opera, Rustic Festival, for the opening of the Tehran Opera House. In 1976 he moved to New York to pursue a doctorate in electronic music composition at Columbia University. He lives between Iran and the USA and continues to work actively as a composer of concert and film music.

Rhapsody for orchestra (1965) by Ahmad Pejman

Nuremberg Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Ali Rahbari (1980)

Published by Colosseum Schallplatten GmbH

As mentioned earlier, Samin Baghtcheban was another important figure in the Iranian music scene and the history of music education. He studied oboe at the Tehran Conservatory of Music and then went to Turkey in 1944 with Hossein Nassehi to study composition at the State Conservatory of Hacettepe University in Ankara. There he met his future wife Evelyn Baghtcheban, a well-known Turkish opera singer and teacher. She was one of the pioneers and founders of opera and choral music in Iran. After Samin Baghtcheban’s return to Iran in 1949, he became a lecturer at his alma mater until 1979. After the 1979 Revolution in Iran, the artist couple moved back to Turkey in 1984. Baghtcheban’s music is based on the folk music of Iran. In 1978 he composed his opus magnum Rangin Kamun, a song cycle for young adults, for soloists, choir and orchestra. He also became known as a translator of Turkish literature into Farsi, especially through translations of works by Nâzım Hikmet, Aziz Nesin and Yaşar Kemal (Unknown, 2020).

Nowruz Too Râhe (New year is on its way) from the Rangin Kamun cycle (1978) by Samin Baghtcheban

Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra and Mitrâ Ensemble , Conducted by Thomas Christian David and Evlin Bâghtchebân (1979)

Published by Mahoor Institute of Culture and Arts

In 1949, the music education system in Iran was divided into two separate music schools, the Tehran Conservatory of Music for Western music and the School of National Music for classical Iranian music. Both institutions operated separately for the next thirty years, training the best generations of Iranian musicians in both styles.

In the same year, Ruhollah Khaleqi (1906-1965), a prominent musician, composer, conductor, author, former student and later assistant to Vaziri, founded the Honarestan-e Moosighi-e Melli (School of National Music) with the intention of teaching exclusively Iranian music. Like his teacher Vaziri, Khaleqi wrote several books and articles on Iranian music theory. His masterpieces are A History of Iranian Music (1954-55), a detailed historiography of musical events in Iran since the Constitutional Revolution (1905) in two volumes (the third volume was completed and published after his death), Harmony of [Western] Music (1941) and A Glance at the Theory of [Persian] Music (1938).

Khaleqi believed in harmonising Iranian music based on the concept of triadic harmony. He composed an enormous amount of music, especially orchestral works. His compositions include instrumental music, lyrical works and songs for voice and orchestra, arrangements of Iranian traditional and patriotic songs for orchestra and numerous hymns. In 1944, he composed the most famous Iranian patriotic song Ey Iran to a poem by Hossein Gole-Golab[3], which became the de facto unofficial national anthem of Iran (Hoseyni Dehkordi & Loloi, 2000).

Ey Iran! (1944) by Ruhollah Khaleqi

Golha Orchestra, Conducted by Ruhollah Khaleqi, Gholâm-Hossein Banân and Abdolvahâb (Vocal)

Compiled and Published by Mahoor Institute of Culture and Arts, Under Supervision of Golnush Khâleqi (2004)

The following influential headmaster of the School of National Music was Hossein Dehlavi (1927-2019), a composer and scholar. He left behind numerous compositions for various media and settings, from solo instrumental pieces to orchestral and choral music, operas and ballets. His music is based on Iranian classical music, and his unique use of Iranian instruments in combination with Western orchestras is still one of the most exciting approaches of the Iranian school of composition. Dehlavi is also the author of the study book for the Tombak, the traditional Iranian soloist percussion instrument.

The following important events in the Iranian music education system occurred in 1965 thanks to Mehdi Barkeshli (1912-1988). He first studied music in Iran in the class of Vaziri and Khaleqi, then acoustics and ethnomusicology in France. Upon his return to Iran, Barkeshli founded the music department of Tehran University, the National Organization for Folklore Music and the graduate programme in musicology at the Tehran School of the Arts. He also founded the Institute for Musicological Research in collaboration with the Royal Foundation for Culture. Barkeshli was also one of the first Iranian musicians to take an interest in the music of mediaeval Iran and ancient treatises on acoustic and historical tuning systems in ancient Persia.

In 1968, Dariush Safvat (1928-2013), an ethnomusicologist, founded the Centre for the Preservation and Dissemination of Iranian Music together with composer Fozié Majd. The institution served to preserve Iran’s traditional music and study historically pure traditional music by inviting the great maestros of the time such as Nur Ali Borumand (1905-1978), Said Hormozi (1897-1976), Yusef Forutan (1891-1978), Asghar Bahari (1905-1995), Abdollah Davami (1899-1980) and Mahmud Karimi (1927-1984) to record and archive their art. They not only performed and interpreted Radif and folklore music in its most authentic form, but also worked to teach the young generation about traditional Iranian music and culture through the original custom (Shafiya, 2017). The students who studied under the guidance of these masters at this institute became the next generation of “true” and “pure” traditional Iranian musicians. Some of them were Mohammad Reza Lotfi (1947 – 2014), Hossein Alizadeh (b. 1951), Parviz Meshkatian (1955-2009), Majid Kiani (b. 1941), Dariush Talai (b. 1953), Jalal Zolfonoun (1937-2012), Mohammad-Reza Shajarian (1940 – 2020) and Parisa (b. 1950) (Bithell & Hill, 2016).

The Golden Years (1950’s to the 1979 Islamic Revolution)

In 1956, the National Ballet Academy of Iran was founded by Nejad Ahmadzadeh and housed in the building of the Tehran Conservatory of Music. Later, in 1967, the company moved to a separate building designed specifically for the dance school. Mehrdad Pahlbod (1917-2018), the nephew of Qolam-Hossein Minbashian and Minister of Culture and Arts of Iran, commissioned Nejad Ahmadzadeh and his wife Haideh (one of Iran’s first ballerinas) to establish a dance school and prepare local students for a possible ballet company in Iran. In 1958, the Iranian National Ballet Company was founded and Nejad Ahmadzadeh was appointed its artistic director (Kiann, 2002). On the recommendation of Dame Ninette de Valois (1898-2001), the founder of the British Royal Ballet, Robert de Warren (1933- ) was invited to Iran in 1965 to work as ballet master and chief choreographer. In addition, at the request of the Minister of Culture, de Warren founded the Iranian National Folklore Society, a centre for folklore dance, a three-year school programme for folk dance and music, which he directed until 1978.

Another significant event of those years in Iran was the construction of the Roudaki Hall in 1957, a performing arts complex influenced by the Vienna State Opera. The building, designed specifically for the performing arts such as opera and ballet, was completed in 1967 and the Iranian National Ballet moved in. In the same year, the Iranian Ministry of Culture and Arts established the Tehran Opera Company (1967) and the Tehran Opera Orchestra (1972). Fakhereh Saba (1920-2007), Monir Vakili (1923-1983) Evelyn Baghtcheban (1928-2010) and Hossein Sarshar (1931-1992) were Iran’s first professional opera singers and the founding members of the Tehran Opera Company. Loris Tjeknavorian (b. 1937), who studied composition with Carl Orff in Salzburg and opera conducting at the University of Michigan, became principal conductor of the Tehran Opera Orchestra from 1972 until its dissolution in 1979 (Petrocelli, 2019).

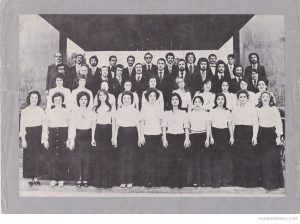

Members of Tehran Opera Company, 1974-1975

Source: ShahreFarang (www.shahrefarang.com/en)

As mentioned earlier, Parviz Mahmoud established the Tehran Symphonic Orchestra (TSO) in 1946 as part of the Conservatory of Music. Now the orchestra flourished as an independent art institution. The following chief conductors of the TSO were Rouben Gregorian (1915-1991) from 1948 to 1951 and then Morteza Hannaneh (1923-1989) from 1952 to 1955.

Gregorian was an Iranian-Armenian composer and conductor who studied in Tehran and Paris and settled in Boston in 1952. Morteza Hannaneh studied French horn at the Tehran Conservatory of Music and then music theory and composition with Parviz Mahmoud. He continued his studies in Italy. After his return to Iran in 1962, he succeeded in founding the Farabi Orchestra. During the eight years of its existence, he led it as chief conductor and artistic director and performed several works by Iranian composers. Like many other Iranian composers and theorists of his generation, his concern was to find a solution to the polyphonisation of traditional Iranian music. In addition to his large collection of compositions for various instrumental settings, from solo piano music to oratorios and several original music pieces for motion pictures, his two books The Theory of Even Harmony (1975) and Lost Scales (1989) are among the most important and creative writings on Iranian music theory.

Heshmat Sanjari (1918-1995) was the permanent conductor of the TSO from 1960 to 1971. He was a student of Vaziri at the Tehran Conservatory of Music and subsequently studied composition and symphonic conducting in Vienna in the class of Hans Swarowsky. His extensive knowledge of Iranian and Western music made him one of the most influential figures in the history of the Tehran Symphony Orchestra. During his engagement as chief conductor and artistic director, the orchestra officially performed the compositions of the younger generation of Iranian composers for the first time. Composers such as Samin Baghtcheban, Ahmad Pejman, Mostafa Kamal Pourtorab (1924-2016) and Houshang Ostovar (1927-2016) were among the lucky ones to hear their scores interpreted. It is important to note that during Sanjari’s leadership, the two most critical Iranian composers and ethnomusicologists also found their way to the TSO, Mohammad-Taghi Massoudieh (1928-1999) and Fozié Majd (b. 1938). In Sanjari’s time, many renowned musicians such as Yehudi Menuhin and Isaac Stern performed with the orchestra under the baton of its chief (Gholami, 2019).

The next outstanding personality in the history of the Tehran Symphonic Orchestra was Farhad Mashkat (b. 1937). Mashkat was born in Germany, studied music at the Geneva Conservatory of Music as a violinist and then composition in New York in 1956 in the class of Henry Cowell and Richard Maxwell (electronic music). He trained as a professional conductor in the class of Carl Bamberger and completed his studies in Italy in 1967 with Franco Ferrara. He was principal conductor of the TSO from 1971 to 1979, when he, like many other Iranians, left the country to live in the USA due to the aftermath of the Islamic Revolution. During Meshkat’s leadership of the TSO, the orchestra began inviting international soloists and guest conductors such as Herbert von Karajan to perform in Tehran. Although the invitations caused controversy in the press because of the Ministry of Arts and Culture’s extravagance with Iran’s annual music budget, the guest artists had a massive impact on Iranian musicians of the time (Gholami, 2019).

To the storm – by Bozorg Lashgari (1923-2018) orchestration and arrangement by Morteza Hannaneh.

Tehran Symphonic Orchestra – Morteza Hannaneh (conductor), Marzieh (1924-2010) (Vocal)

Roudaki Hall, Tehran, Iran. (1968)

Meshkat was also one of the main conductors of the Shiraz Arts Festival since 1967. His aim was to introduce avant-garde and modernist music to the Iranian public. He commissioned Alireza Mashayekhi (b. 1940) to compose for the TSO after Mashayekhi returned to Iran in 1970. He was also the conductor of almost all orchestral works by Emanuel Melik-Aslanian (1915-2003), a student of Paul Hindemith in Germany and one of Iran’s greatest teachers of composition and piano.

The existence of the Tehran Symphonic Orchestra, the Iranian National Ballet Company and the Tehran Opera Company provided a great opportunity for the new generation of Iranian composers to compose for larger musical forms such as oratorios, cantatas, operas and ballets. Zal-o Roudabeh (1968) by Samin Baghtcheban, Jashn-e Dehghan (1968) and Delavar-e Sahand (1969) by Ahmad Pejman, Khosrow Va Shirin (1970) and Mani va Mana (1978) by Hossein Dehlavi or Pardis va Parisa (1970) by Loris Tjeknavorian are some of the most critically acclaimed Iranian operas written during this period. Bazi-ha (1966) by Ahmad Pejman, Stone statue (1968) by Fozié Majd, The myth of creation (1971) by Melik-Aslanian or Bijan va Manijeh (1976) by Hossein Dehlavi are some of the most important Iranian ballets composed before the 1979 Islamic Revolution.

Close Encounter of Traditionalism and Avant-garde

In 1967, Farah Pahlavi (b. 1938), the former Shahbanu (Empress) of Iran, who was committed to promoting art and culture in Iran, founded the Shiraz Art Festival. Her preoccupation with the traditional and ancient art of Iran and, on the other hand, her passion for contemporary and modern art of the world made her the biggest promoter of cultural events and initiatives in Iran during her reign. The Shiraz Art Festival was one of her creative ideas to build a bridge between traditional and modern art in the ancient capital of Iran, Shiraz-Persepolis (550 – 330 BC).

The other aim was to present the traditional art of Iran and to introduce the modern and contemporary art of Iran to the international audience. The idea of holding an international festival was to “nurture the arts, pay tribute to the nation’s traditional arts and raise cultural standards in Iran” and “ensure wider appreciation of the work of Iranian artists, introduce foreign artists to Iran, and acquaint the Iranian public with the latest creative developments of other countries.” The influence of Western contemporary and avant-garde art on Iranian artists, and conversely the influence of traditional Iranian art and thought as a source of inspiration for the Western artists who visited Iran during these golden years of the Shiraz Arts Festival, represent the most important legacy of cultural exchange and the pursuit of the arts in the 1960s and 1970s (Afshar, 2019).

The festival hosted many internationally renowned artists such as Jerzy Grotowski, Peter Brook, Tadeusz Kantor, Peter Schumann, Robert Wilson, Shūji Terayama, Merce Cunningham, Maurice Béjart and many more in the field of contemporary and modern theatre and performing arts. Audiences could hear music by and in the presence of composers such as Iannis Xenakis, Bruno Maderna, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Krzysztof Penderecki, Morton Feldman, John Cage, David Tudor or Gordon Mumma. Their works have been performed alongside performances of the traditional arts of Asia, Africa and Latin America, Indian Raga music, Bharatanatyam and Kathakali, Qawwali, the music of Afghanistan, Egypt, Iraq, Korea and Vietnam, Balinese Gamelan, Japanese Nôh, the drums of Rwanda, traditional dances of Bhutan, Senegal, Uganda and Brazil. Traditional and regional music and dramatic performance arts from Iran were performed, such as Ta’zieh (passion plays), Naqqāli (Iranian dramatic storytelling), Siah-Bazi (Iranian satirical folk play) or Ru-Howzi (improvised comic play about domestic life) (Afshar, 2019).

In 1966, Vahe Khochayan (1929-2015) founded the National Iranian Television Chamber Orchestra (NITV Chamber Orchestra). He studied music as a violinist at the Tehran Conservatory of Music and then at the Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia in Italy. After returning to Iran, he began working at the Tehran Conservatory of Music as a teacher and conductor.

The National Iranian Television Chamber Orchestra became the main orchestra of the Shiraz Arts Festival and played mainly Western repertoire, occasionally supplemented with compositions by Iranian composers, which became more frequent in the later editions of the festival. The NITV Chamber Orchestra focused on commissioning works from a younger generation of Iranian composers. Several prominent conductors, including Vahe Khochayan, Austrian Thomas Christian David (1925-2006) and Morteza Hannaneh, have led the orchestra throughout its history. Another prominent conductor was Farhad Mashkat, who championed the performance of many compositions by Iranian composers, including a performance of Caprice for piano and orchestra by Morteza Hannaneh in 1968, Prelude & Fugue in Dashti by Hormoz Farhat (1928-2021) or Impressions for string orchestra by Houshang Ostovar (1927-2016).

Karlheinz Stockhausen at Seraye Moshir, Shiraz, 1. Sept. 1972.

Source: Stockhausen-Verlag, Stockhausen Foundation for Music www.stockhausen.org

At the 1973 Shiraz Arts Festival, Catherine Comet (b. 1944) conducted May 1973 by Dariush Dolatshahi and Shabkuk, a masterpiece for string orchestra by Fozié Majd, in collaboration with the NIRT Chamber Orchestra. Fozié Majd, composer and ethnomusicologist, who took piano lessons from Emanuel Melik-Aslanian at a young age, moved from Iran to study music theory and composition at the University of Edinburgh and then ethnomusicology under the guidance of Trần Văn Khê at the University of Sorbonne. Thanks to a special scholarship from the French government, she became a student of Nadia Boulanger. After returning to Iran, she devoted herself to the study of traditional Iranian music. She is one of the pioneers of avant-garde music in Iran, and her music is based on her deep understanding of Iran’s regional music. Majd is also one of the first ethnomusicologists to collect and archive Iran’s regional and folkloric music. In the 1970s, she composed music for experimental and avant-garde theatre and films, and composed for various instrumentations, from solo to chamber music to ballet. In the last forty years, she has focused mainly on composing music for solo piano and the analysis of the regional music of Iran (“Fozié Majd | Divine Art Recordings”, 2019).

Another important premiere during the 1974 Shiraz Arts Festival belonged to Alireza Mashayekhi when Diego Masson (b. 1935) performed his composition Permanent op.33 for fifteen string instruments. Alireza Mashayekhi studied piano and composition in Iran and then in Vienna with Hanns Jelinek and Karl Schiske. He continued his studies in electronic music at Utrecht University in the class of Gottfried Michael Koenig, where he completed his composition Shur Op.15 in 1968, the first Iranian work for electronic music (Nettl, 1987). Alireza Mashayekhi is considered the pioneer of avant-garde and modern music in Iran. He is the most active Iranian composer with an extensive collection of works for various media, from purely electronic music to symphonic orchestras accompanied by electronics, and from solo instruments to a mixture of Iranian and Western instruments, from chamber music to orchestral forms. His music is the result of his deep understanding of Western and Iranian culture and philosophy. He dedicated his life to the promotion and dissemination of new music in Iran (Gluck, 2011).

In 1976, Ivo Malec (1925-2019) conducted Hell was but the sparkle of our futile suffering by Fozié Majd and From Behind the Glass for strings, piano and tape echo by Dariush Dolatshahi, which was a Festival commission. In the same year, the American Brass Quintet performed Contradictions by Alireza Mashayekhi. In 1977, Maurice Le Roux (1923-1992) repeatedly conducted Permanent op.33 by Alireza Mashayekhi as well as the compositions In memory of Ravel by Iradj Sahbai (1945), A piece for strings by Massoud Pourfarrokh and Rhetorics for piano & strings by Hormoz Farhat.

“Sound the Trumpets Beat the Drums” (1969)

SHIRAZ ARTS FESTIVAL ’69: Documentary BY Tony Williams

Music in Iran after 1979

After the Islamic Revolution of 1979 and the Cultural Revolution of 1980, almost all musical activities in Iran came to a halt. All music schools and the music department of Tehran University were closed. All functioning orchestras were disbanded with immediate effect. The national ballet and opera companies were closed and have not been reopened to this day. Hymns, revolutionary and patriotic songs were the only music allowed in the next few years, especially songs that referred to the war and supported the spirit of the soldiers who had fought during the eight-year war between Iraq and Iran (1980 – 1988).

In the 1980s, the Tehran Symphony Orchestra was the only orchestra to survive the dark days of revolution and war. The institution performed very few, highly limited events, and the need for more performers to support the orchestra’s weakened core was one of the biggest problems, as many top Iranian musicians fled the country with the rise of the new Islamic regime. Three years after the Islamic revolution, Nader Mortezapour (b. 1952) became principal conductor of the TSO, hoping to return to earlier work schedules. In 1985, however, the orchestra was ordered to disband. It only performed at a few special events, mostly with local Iranian guest conductors and mainly for propaganda reasons of the new regime. In 1990, Fereydoun Naseri (1930-2005) was appointed chief conductor of the reopened TSO. He was a student of composition and music theory in the class of Samin Baghtcheban and a graduate of the Royal Conservatory in Brussels. The TSO resumed its work but has not yet returned to the days of its greatness before the 1979 revolution. In the last twenty years, the artistic direction of the orchestra changed quite frequently. Among the following chief conductors of the TSO, Ali Rahbari (2004-2005 and 2015-2016), Nader Mashayekhi (2006-2007), Manuchehr Sahbai (2007-2010) or Shahrdad Rohani (2016-2020) have anchored their names in the history of this institution by introducing ambitious programmes and trying to return the orchestra to its former greatness. The composer and conductor Nader Mashayekhi (b. 1958) deserves a special mention. He studied at the Tehran Conservatory of Music and then moved to Austria to continue his education at the University of Music and Performing Arts in Vienna under the direction of Roman Haubenstock-Ramati. During his years as principal conductor of the TSO, Nader Mashayekhi strove to revive the repertoire of contemporary classical music by including at least one piece of contemporary music per week in his concert programme. After him, Rahbari, Sahbai or Rohani tried to include more contemporary compositions in the orchestral repertoire, but the choice of music was usually very limited and exclusionary; the TSO still focuses mainly on performing famous classical, romantic and late romantic works.

Tehran Symphony Orchestra and the national choir performing in Tehran’s sports complex in one of the first celebrations of Islamic the revolution (Year unknown – Probably between 1982 to 1985)

In 1984, the Tehran Conservatory of Music and the School of National Music were merged and became the “School of Revolutionary Music and Songs” with two separate buildings, one for boys and one for girls. After several years of discussions, controversies and disputes about the existence of this musical institution, the name of the school was changed back to Tehran Conservatory of Music, but divided into two separate branches according to the gender of the students.

In 1988, the music department of Tehran University resumed its work, with a minimal offer of study places and training branches. In 1991, another institution, the Music Department of Tehran University of the Arts, was established, offering its students music education in two departments: military music and a bachelor’s degree in music performance and composition.

In the early 1990s, official music teaching was reintroduced, but apart from being accepted and allowed to work, the need for qualified music teachers continued to be a serious problem in Iran. All Western teachers and musicians, as well as most Iranian musicians who had worked in music institutions before the 1979 Islamic Revolution, immediately fled the country or were forcibly deported. The gloomy and unpromising situation of the revolution and the difficulties of the Iran-Iraq war caused many Iranian musicians to emigrate to the West, where they could continue their careers. Very well-known and highly acclaimed composers such as Hossein Aslani (1936-2020), Golnoush Khaleghi (1941-2021), Sheida Gharachedaghi (b. 1941), Reza Vali (b. 1952), Behzad Ranjbaran (b. 1955) and Shahrokh Yadegari (b. 1961) are among the many other Iranian composers and artists who have emigrated to the United States and pursued highly successful artistic and academic careers in their new homeland.

But fortunately for the next generations of artists who grew up in the country, there were some established composers who lived in Iran in the 1980s and 1990s, dedicated to their work and determined to stay and share their musical knowledge with anyone who wanted to study music. One of them was Mehran Rouhani (b. 1946), who studied composition in Iran in the class of Hormoz Farhat and Alireza Mashayekhi and then continued his studies at the Royal College of Music in London in the class of Sir Michael Tippet. On his return to Iran, Rouhani became a lecturer at the Tehran Conservatory of Music. After the 1979 Islamic Revolution, he began teaching in his home office as a private music teacher. He guided many young students to create the next generation of actively working musicians in Iran.

Shahrokh Khajenouri (b. 1952) is another critical composer and educator who did much good for Iranian music education after the 1979 Islamic Revolution. At a young age, Khajenouri studied piano and music theory with Emanuel Melik-Aslanian. In 1971, he moved to England to study electronic music and music technology at Morley College of London. At the same time, he took lessons in classical composition at the London Academy of Music. He returned to Iran in the early 1980s. Since then, he has been giving private music lessons in his home office and was appointed a lecturer at the University of Arts in Tehran in 1997.

After the Islamic Revolution, Alireza Mashayekhi left Iran to continue his research and studies abroad. After returning to Iran in 1993, he founded the Tehran Contemporary Music Group (1993) with his old friend and colleague Farimah Ghavam-Sadri (b. 1950), an exceptional pianist and teacher. The aim of the Tehran Contemporary Music Group was to introduce new music to Iranian audiences and to promote young composers and performers. Soon after, the Iranian Orchestra for New Music (1995) was founded, in which Mashayekhi proposed to unite Iranian and Western instruments in a performance framework. Under the direction of Mashayekhi and Ghavam-Sadri, a new festival “Classic to Modern” was launched to present the repertoire of Western classical music and new compositions by Iranian composers, especially those of the younger generation and particularly the students of Alireza Masahyekhi. At the time of writing this article, the festival has reached its eighth edition (2019), making it the longest independently organised music festival in Iran after the Islamic Revolution.

Alireza Mashayekhi conducts “the new music orchestra” at Classic to Modern Festival

Source: Mehr News – Iranian news agency

Kayvan Mirhadi (b. 1960) is another important musician who has contributed to preserving music in Iran over the last forty years. He is a classical guitarist, composer and conductor who studied music theory and composition at the private classes of Mehran Rouhani. His home office became one of the most famous and important meeting places for the younger generation to learn about contemporary music, discuss art and philosophy, and exchange books and CDs of contemporary and classical music. Besides the opportunity to talk about art, Mirhadi contributed to Iranian music education with his translation of Paul Griffiths’ “Modern Music: A Concise History from Debussy to Boulez” in early 2000, which was for a long time the only source for modern music in Farsi. He is also the founder of one of Iran’s first private orchestras, the “Camerata Orchestra”, which performed mainly international contemporary classical composers such as Peteris Vasks, Philip Glass or Arvo Pärt.

Turkmen by Kayvan Mirhadi

Camerata Tehran Orchestra, conducted by Kayvan Mirhadi

It was only after the 1997 presidential elections, when the reformist clerk Mohammad Khatami (b. 1943) became the fifth president of the Islamic Republic of Iran, that the country felt a slight shift towards more freedom. During Khatami’s tenure, the country’s policy in international relations slowly changed from confrontation to reconciliation. Iran expanded its relations with other countries for the first time after almost two decades of separation (Alam, 2000). The impact of access to PC with an expensive and slow dial-up internet connection in the late 1990s and early 2000s changed access to information for many in Iran. In the context of this article in particular, PC and the internet connection miraculously opened up the next generation of Iranian musicians to the international world. It gave them access to new music, the ability to gain knowledge, listen to music online and watch videos over the internet was like a godsend for young Iranians. Before the internet, music cassettes (later CDs and DVDs) or books about music or sheet music and scores were only available in a few shops in Tehran or larger Iranian cities. In order to comply with Islamic values and the tastes of the shopkeepers, these shops usually offered only very limited material. The internet has lifted these restrictions, overriding the dependence on stubborn shopkeepers, censorship and, most importantly, the enforced taste of a particular genre or style.

Government officials never seem to understand the importance of creating a conducive environment for the flourishing of art and culture. Moreover, it is the government’s duty to support and develop the arts and music of their country. To date, there is no support or assistance programme for artists in Iran, no support structures in the ministries and no private institutions that help musicians. The government only supports projects related to populist art or propaganda-oriented art and music. Even without their help, the number of independent artists and artistic events in the country has continued to grow. The most convenient place to start a music career has always been a private music institute, as both children and adults could take lessons there. Since the only state music schools are in Tehran, Tabriz and Isfahan and it is extremely difficult to get into them, taking lessons at a private music institute is the best way to get a musical education. In addition, private lessons are still offered. However, to be accepted by a particular musician, one often has to wait a long time to get a place. Although there were no proper learning aids or good resources such as audio libraries or books and scores, only the thirst for the unknown and the love of the older generation to pass on their knowledge ensured that classical and new music became part of society. The role of private orchestras and ensembles in Iran is crucial for the continuation of intellectualism and artistic music. While the state-funded orchestras only perform a certain type of classical music (either Western music from the classical-romantic era or the composers supported by the government), the private orchestras contribute to the diversification of musical genres in Iran and include Iranian composers in their repertoire.

In the last 10 to 15 years, international activities in the Iranian music scene have increased enormously. One of the reasons for this could be the internet age. The other reason is that many Iranian musicians outside Iran want to contribute to the musical life in the country. They want to organise artistic activities and establish an art exchange on an international level. Especially the younger generation of Iranians born between 1970 and 1990, who had the opportunity to go abroad and complete their education outside Iran, are returning to the country and trying to get involved in teaching, curatorial activities, organising concerts and educational projects.

The last ten years in the history of music education and popularisation of classical and contemporary music in Iran are full of many beautiful achievements. The Yarava Music Group is one of the longest running artistic communities in Iran. They organise private concerts, lectures and festivals and even have their own publishing label for the production of audio CDs. The Yarava Music Group, founded in 1999 by Mehdi Jalali (b. 1980) in Tehran, focuses on performing new music, especially the works of Iranian composers such as Fozié Majd, Shahrokh Khajenouri or Kiawasch Sahebnassagh (b. 1968). Jalali and his group mainly support the close circle of friends and colleagues who studied music together in Tehran and became important personalities of the Iranian music scene. In 2019, their project “Berlin-Tehran travellers”, an artistic exchange between Iran and Germany, deserves greater attention through the commissioning of music by Fozié Majd and Shahrokh Khajenouri.

Parasita Amoroso Op.129 (2008) by Shahrokh Khajenouri

Performed by Yarava Modern Orchestra

Niavaran Cultural Center, Tehran Iran 8 November 2008

One of the most groundbreaking events in the history of contemporary and experimental music in Iran was the establishment of the Tehran Contemporary Music Festival (TCMF), a self-sustaining international music festival focused entirely on contemporary and experimental music. TCMF not only offers an extensive concert programme, but also seeks to promote young and emerging Iranian musicians and give them the opportunity to learn more about contemporary music. The festival organises educational events such as lectures, workshops and master classes led by internationally renowned Iranian and foreign artists. TCMF was founded by Navid Gohari (b. 1984) and Ehsan Tarokh (b. 1981) together, with Martyna Kosecka (b. 1989) and Idin Samimi Mofakham (b. 1982) as artistic advisors and international artistic directors. Since the first edition in 2016, TCMF has had the pleasure of hosting artists from Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Finland, Georgia, Germany, Italy, Poland, Sweden, Switzerland and most importantly many established and emerging Iranian contemporary music ensembles, orchestras, soloists and composers.

Music for Everyone Initiative – Steel Plates Project, performance at Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art / Second Tehran international contemporary music festival 2017

The Nilper Orchestra was founded in 2004 by Navid Gohari and has been one of the most active private orchestras for two decades. It is dedicated to promoting contemporary music and focuses mainly on commissioning and performing new music for the younger generation of Iranian composers. The Nilper Orchestra, the main orchestra of the TCMF, has commissioned and premiered several newly composed orchestral pieces by Iranian and non-Iranian composers during recent festival events.

Concerto for Guitar and String Orchestra by Ardavan Vossoughi

World Premiere at Tehran Contemporary Music Festival

Nilper Orchestra, Navid Gohari (Conductor) Renata Arlotti (Guitar)

The Iranian Female Composers Association (IFCA) is another important initiative worth mentioning. IFCA was founded in 2017 by three remarkable female composers: Niloufar Nourbakhsh (b. 1992), Anahita Abbasi (b. 1985) and Aida Shirazi (b. 1987). As they mention on their website, IFCA is a platform to support, promote and celebrate Iranian women in music through concerts, public performances, installations, interdisciplinary collaborations and workshops. Their aim is to empower Iranian women in music and the arts by promoting originality, honouring diversity and strengthening equality. Since 2017, they have organised several international events focusing on the music of Iranian women composers.

Epilogue

Finding the right way to end this article without falling into nostalgia is a greater challenge than writing the article itself. As the reader could already gather from the lines of this article, the history of classical music in Iran had a long and hard road until it became what it is today. It was never an easy road; there was always a struggle between modernism and conservatism, with one gaining more dominance than the other. Even today, this struggle continues between many Iranian musicians who believe that they do not need Western music in Iran and others who firmly believe that traditional music is worth nothing. Fortunately, the number of Iranian artists who believe in a balance between Iranian and Western musical art is constantly growing.

A certain nostalgia comes over me when I think of all the composers and artists mentioned in my contribution. I dream of the day when the music of the composers mentioned in this article, especially those who have passed away, will be performed in Iran and in the world, and I hope and fight for their music to be included in the repertoire of orchestras and ensembles worldwide. There are also so many unfinished or unperformed operas, ballets, music theatre, symphonic pieces and projects initiated by the older generation of Iranian composers such as Alireza Mashayekhi, Fozié Majd, Ahmad Pejman and many others, which have unfortunately become an invisible graveyard of musical works abandoned in the abstruse history of recent times. I wish that the great Iranian composers complete their unfinished masterpieces and premiere their music in Iran while some of them are still able to do so. Above all, I hope that these wishes will be granted with the support of many.

Tehran, Iran (June 2019) – Oslo, Norway (July 2020/January 2023)

References

Advielle, V. (1885). La musique chez les Persans en 1885.

Afshar, M. (2019). Shiraz arts festival, 1967 1977. Iran Namag, 4(2), 4–64.

Alam, S. (2000). The changing paradigm of Iranian foreign policy under Khatami. Strategic Analysis, 24(9), 1629–1653. https://doi.org/10.1080/09700160008455310

Asadi, H. (2001). Massoudieh, Mohammad-Taghi. In Oxford Music Online, Grove Music Online.

Bastaninezhad, A. (2014). A historical overview of Iranian music pedagogy (1905-2014). Australian Journal of Music Education, 2014(2), 5–22. Retrieved from here.

Bithell, C., & Hill, J. (2016). The Oxford handbook of music revival. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Darvishi, M. R. (1994). Westward Look, A Discourse on the Impact of Western Music on Iranian Music. Mahoor Institute of Culture and Arts.

Dehbashi, A. (2018). In dialogue with Abdolhamid Eshragh (part III). Harmony Talk, Online Journal of Music.

Diba, L. (2013). The Formation of Modern Iranian Art: From Kamal-al-Molk to Zenderoudi. Iran Modern. Retrieved from here.

Farhat, H. (2003). VAZIRI, ʿAli-Naqi. In Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved from https://iranicaonline.org/articles/vaziri-ali-naqi

Farhat, H. (2004). The dastgāh concept in Persian music. Cambridge ; New York: Cambridge University Press.

Fozié Majd | Divine Art Recordings. (2019). Retrieved January 11, 2023, from DIVINE ART RECORDINGS website.

Gholami, M. (2019). Iranian Contemporary Flute Music: An Analysis of Kouchyar Shahroudi’s Dances Mystiques (2017) and Kiawasch SahebNassagh’s Amusie (2018) for flute and piano (pp. 22–23). Texas Christian University. Retrieved from here.

Gluck, B. (2011). Conversations with Alireza Mashayekhi, Iranian Composer. EContact. Retrieved from here.

Gluck, R. (2007). The Shiraz Arts Festival: Western Avant-Garde Arts in 1970s Iran. Leonardo, 40(1), 20–28. https://doi.org/10.1162/leon.2007.40.1.20

Ḥoseyni Dehkordi, M. (2005). MINBĀŠIĀN, Ḡolām-Ḥosayn. In Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved from here.

Hoseyni Dehkordi, M., & Loloi, P. (2000). EY IRĀN. In Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved from here.

Kayvan, Y. (2008, February). Iranian Symphonic Music in 1979 Revolution. Harmony Talk. Retrieved from here.

Khāliqī, R. A. (2003). سرگذشت موسيقى ايران – The history of the Iranian music (S. Sepanta, Ed.). Mahoor Institute of Culture and Arts. (Original work published 1974)

Khoshnam, M. (2011, December 29). یادی از پرویز منصوری؛ موسیقیدان و آموزگار موسیقی. Retrieved January 8, 2023, from BBC News فارسی website.

Kiann, N. (2002). Les Ballets Persans | Nima Kiann – History. Retrieved January 10, 2023, from www.artira.com website.

Mohebi, A. (2005). Abolhasan Saba. Aftab Magazine.

Nettl, B. (1987). The Radif of Persian Music. Indiana University.

Petrocelli, P. (2019). The Evolution of Opera Theatre in the Middle East and North Africa. Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Pourghanad, S. (2018). Minbashian, the man of first steps. Harmony Talk, Online Journal of Music.

Shafiya, R. (2017). Calm and restless; a memory of Dr. Dariush Safvat. Mahoor Institute of Culture and Arts.

Unknown. (2004, October 20). On the anniversary of the birth of Fereydun Farzaneh. ISNA (Iranian Students’ News Agency). Retrieved from here.

Unknown. (2019, September 28). Hossein Nassehi, National pioneer of musicology in Iran. IRNA (Islamic Republic News Agency). Retrieved from here.

Unknown. (2020, March 19). Author and influential figure in Iranian polyphonic music. Retrieved April 25, 2020, from IRNA (Islamic Republic News Agency) website.

- Nasser-al-Din Shah was the king of Iran from 1848 until 1 May 1896, when he was assassinated [author.] ↑

- Mohammad-Ali Foroughi, was a teacher, diplomat, nationalist, writer, and politician. He was the writer of the first book on Western philosophy (the course of wisdom in Europe) in Farsi [auth.]. ↑

- Hossein Gole-Golab (1895-1985) was an Iranian scholar, musician and poet [auth.]. ↑