Micro-moments

A New Media Journey in Iran

Dear Idin and Martyna,

I am writing to you with a great delay caused by many different reasons, some of which I’m going to explain here, but before we start let me say that these are not excuses of me being late or responding to your invitation with less attention and care, but rather I have been thinking about a format which can portray the most the fragmented situation we are in without falling into the trap of self-victimizing or …

As I write these lines, there has been a tremendous amount of rapid changes in our country, and a worrying gap between the fragments of Iranian Society which makes us think about the Arts and its role in our society even more. The fact that overnight announced fuel price policies had resulted in escalating nation-wide unrest and state violence that took the lives of many citizens. To deal with the impact of spreading the news unplugging the whole country’s Internet connection would have been unimaginable and unprecedented. Both shocks left the majority of the middle class in a crippling trauma.

40 days past, we are thinking of a possible future and the role was once by the majority of old media(s) we’ve known and perceived in our lives, the rapid pace of the replacement of those and how we feel nostalgic about them.

Therefore, I chose the format of a letter rather than a regular essay, as it gives me an option to recall some micro-histories on how we used to encounter New Media(s) in the context of post-revolutionary Iran, some of these I had the chance to be old enough to remember and other the opportunity to witness myself. In writing/recalling other moments, I also refer to memoirs, Interviews (some of which I made myself with certain individuals) the one I could find through papers published on Iranian Contemporary art Internationally, all referenced at the bottom of this long letter, making it more look like a proper paper!

These micro-moments of encounter are mapped through four decades and a bit further.

The Tehran of the 90s was not really acquainted with media arts( the worn-out term coined around 60s -70s); The limited number of art galleries and cultural institutions preferred to stick with the norms and were devoted to traditional media such as painting and sculpture and seldom photography. Though in countries like the UK and Us the Video became an excitingly immediate medium for artists after its introduction in the early 1960s, video or video art is a relatively young medium in the Iranian art scene, and its history goes back only to the mid-1990s. I will refer to the reasons behind the belated emergence of media arts and its troublesome and often misleading definition and the impact of the socio-political and economic factors for its current popularity as a cheap way of recording and representation later.

Before that, I believe it’s noteworthy to refer to the pioneers in the field to determine the artistic legacies and assess our relation to them. Ars Poetica by Khosrow Sinai (experimental short film about Jazeh Tabatabai’s (avant-garde painter, poet, and sculptor) can be considered among the first vide artworks. Manouchehr Tayyab’s The Rhythm, a short documentary on Hossein Tehrani and his drum can be classified as one of the first music videos, among others.

Historical Context : How and When did photography become accessible to Iranian people?

Reaza Sheikh , a Photography historian, in an essay titled “the man who would be the king” states ” Patronage of the Qajar Shah was instrumental in paving the way for the entry of photography into Iran in the mid-nineteenth century as a means to commemorate the self of a select few in the form of portraits in studios. Euphoria surrounding the Constitutional Revolution democratised portraiture in Iran for a short period, when the crowds stepped into the public arena in unprecedented numbers and photographers stepped out of their studios to record history in the making.”

Though the emergence of photography as a democratic medium in the hands of modern citizens is considered to be circa 1950 which is concurrent with the emergence of the middle class in the 1950s, the increase in number of camera shops in cities in Iran and the number of photography-related advertisements in various journals, one can surmise that photography was one of the main preoccupations of this class during these years. As a result, “photography was to serve the needs and meet the desires of a wider spectrum of society. A new range of citizens had stepped up to the fore. They were an emerging middle class, many of whom took up photography as amateurs during the following decades.” [1]

Regarding these points, one can conclude that this allows the developments of new ways of expression and the chance to record all aspects of daily life, aligned with the ancient desire to be remembered in/for the future.

The emergence of Cinema Azad which started independently and after a while affiliated/supported with the state television caused a countrywide proliferation of small initiatives circled around the experimental use on 8 mm (and possibly 16 mm) cameras. Young filmmakers and newcomers often star in their friends’ films for help with the set or the editing of their films.

- Free Cinema (Sīnamā-yi Āzād), considered as the “experimental” (Tajrubī) cinema of Iran, was an avant-garde movement that distanced itself far from the narrative commercial and alternative cinema. Free Cinema was first founded through the collaboration of a number of young directors. With the financial support of the National Television, according to Jamal Umid (a filmmaker and co-founder of Free Cinema), Free Cinema took a more solid form.127 The group showcased their own short films, mostly made as amateur school projects and theses, and later on – after they became better known among the public and cineastes – they started holding screening and discussion programs about prominent filmmakers. Eventually, the group also established a film festival and journal publication by the same name. In 1969, Firdawsi magazine supported Iran’s “amateur cinema” that had recently found the opportunity to screen a number of its films at Iran’s Kānūn-i Fīlm (Film Association), “the only healthy cinematic environment” in Iran.128 In a report on an “amateur film” entitled The Eyes (Chashmhā, 1969), Basīr Nasībī reveals to the reader that the amateur cinema of Iran, which resembled an avantgarde cinema, had begun with the short film, The Blood of a Memory (Khūn-i Yik Khātirah). The Eyes by Ibrāhīm Vahīd-Zādah included “new thoughts in a new form,” “a subjective ambience” and “a symbolic expression”; overall, it was a film that, according to the author of the article, demonstrated the director’s “hatred for a ‘storytelling’ cinema.”129 In an interview with the director in Nigīn magazine, Arby Ovanessian and Basīr Nasībī also praised the film for its new form amid “the vexatious bazaar of Film-Farsi.” [2]

- While the proponents of the operation of video clubs were mostly concentrated in the Plan and Budget Organization, the opponents came from the Ministry of Islamic Guidance. A report22 published six months after the banning of video clubs in December 1983 reflected the debate among the officials. The Plan and Budget Ministry, which later became an “organization,” is responsible for general policy-making and the allocation of appropriate budgets to the governmental ministries. The cultural experts of this organization had pointed to the existence of an underground black market in Iran, and argued that the ban policy has not halted the sale and distribution of video machines and tapes. On the question of why people resort to VCR, they had pointed to the role of video in filling people’s leisure time in a period when the import of foreign films had been banned and “drab” programs had dominated television and cinema screens. Rejecting any cynical exaggeration of negative video effects, they emphasized the potential of this technology, and urged the government to intervene actively in this economic and cultural activity in order to counter the black market profiteers. In contrast, the pro-ban campaigners accused video clubs of circulating unauthorized video materials, and argued that if a black market for video machines and tapes exists, we have to blame the customs department and the legal system! Within a framework similar to that of the “hypodermic needle” model of media effects, and from a protectionist perspective, they considered the video audiences as passive and vulnerable in the face of “devastating” and “disastrous” effects of video. In addition, they argued that cinema and television programs are “drab” only for a minority of the Iranian population: video audiences. Opponents of the video clubs’ activities based their opposition on their perceptions of the presumed political and socio-cultural effects of the video in Iranian society. They pointed to three types of effects: political, socio-cultural, and economic, and accordingly called for protecting the newly established revolutionary Islamic Republic, Islamic.[3]

- Tired of the incessant war coverage and sermonizing, television audiences have turned to VCRs, preferring to rent videos. VCRs are now widespread amongst urban families. A VCR costs approximately 100,000 tomans, about $1,000 at black-market currency rates. In big cities, especially Tehran, the numerous video stores of 1983 have been reduced to a handful, yet the most current foreign films and soft porn are available on the extensive “cultural black market,” brought in via Dubai and the Arab Emirates.

There is a large market for audio cassettes, both of Persian classical music and foreign music. Weekly news cassettes have also been devised which provide information, analysis, and music and are sold by street vendors.

The proliferation of homemade alcohol and black-market video show the boomerang effect of a centrally-devised and coercive cultural and communications policy.

Thus attempts at ideological hegemony may be derailed by popular cultural resistance; such resistance may eventually be “tolerated” if this resistance is perceived to make no very specific political claims nor present any great threat to the regime’s actual political control—becoming a new form of “repressive tolerance,” as Marcuse once described the process.

These moments from my point of view could be a usful indicator to be included in a draft (yet imagined) timeline, if we manage to access these often undocumented/less articulated happenings and progression, and doing so might give us a clue for a possible multulayered history of New Media Arts in Iran in the past 50 years.

- Contest,1976: Kamran Diba exhibition held at the Zand Gallery (directed by Famous Artist/collector/designer Fereydoun Ave) reflected the influence of the British artist Allen Jones as well as the pop art movement. With the help of a photographer friend Ahmad Ali, Diba photographed the shoes of audience members at the gallery. The concept behind the show derived from a sweet childhood memory of a local shoemaker and was connected to his mother’s love of shoes. “This was my first childhood exposure to someone making a fuss over proportion, style, and design details,” he said at the time. [4]

Inspired by the Pop art Mania at the time and with an eye on ever-growing Western culture influence in Iran, This could be considered one of the early example of participatory happening, I would have been great if there was a video available of the event but what we are left with about this is the memoir of Kamran Diba and few photos of Ahmad Aali from the Contest happening.

In a follow up event in 1998 that I witnessed myself, another house destined to be demolished in Shariati Ave. The project was somehow advertised in a low profile way, Can’t remember exactly how I was informed as an art student back then, I walked in shyly to encounter a black and red poster by graphic designer Reza Abedini printed in silkscreen to support the project, The Group Project “the experiment 77” changes my artistic life forever.

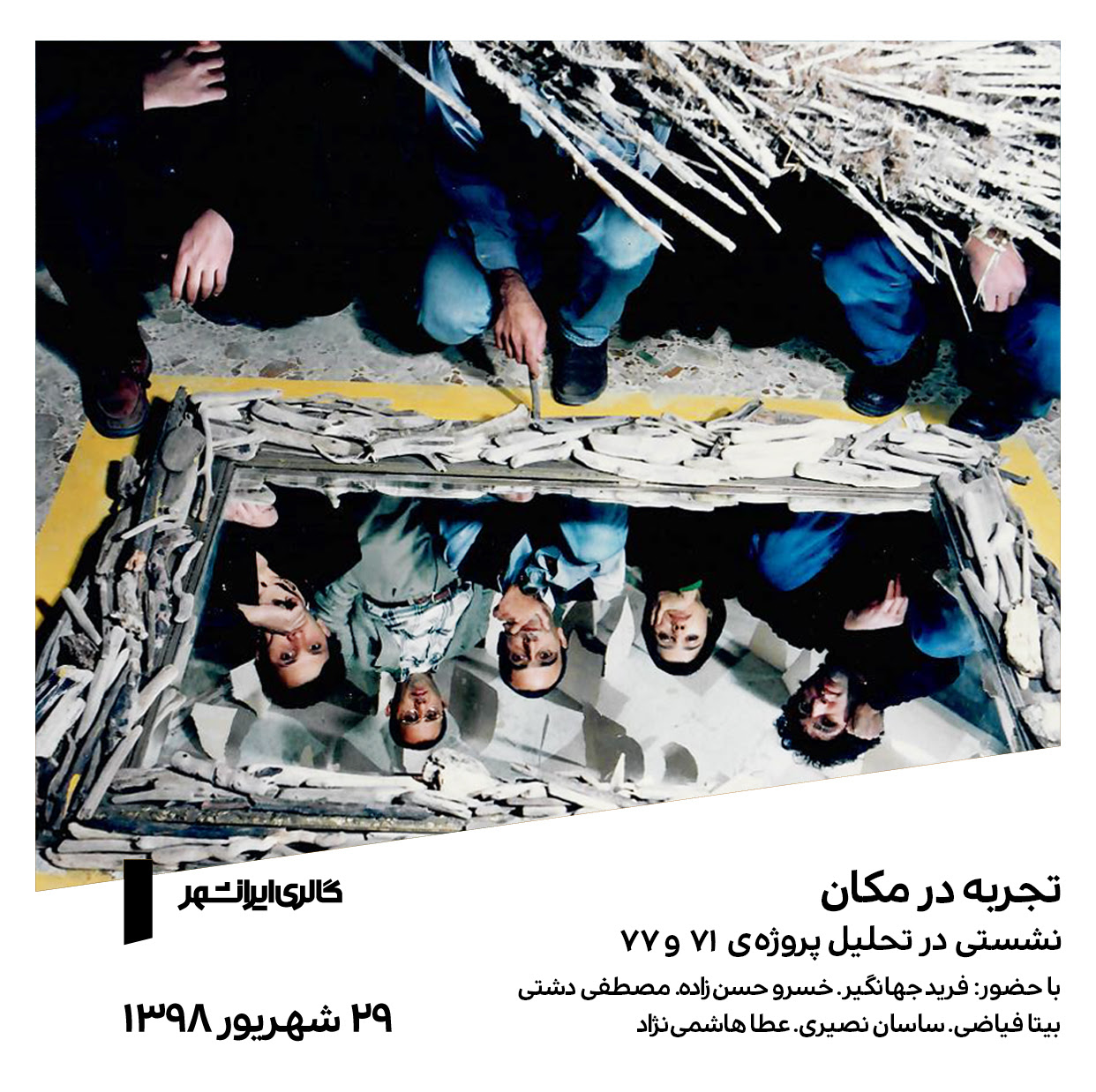

Tavoos Magazine’s Columnist Shahla Etemadi Writes: […] Pursuing that line of thought, from April 23rd to 31st 1998, we witnessed an exhibition entitled Experience 77, held by the Contemporary Art Workshop. This exhibition was held in a shabby house and, following the death of Shahrokh Ghiassi and in the absence of Mostafa Dashti, had taken shape with the cooperation of the remainder of the group with, Bita Fayyazi, Khosrow Hassanzadeh and `Ata Hashemi.[…]

Sassan Nassiri had adopted “meaning” as his theme and utilized roots and stems broken loose from the seashore and objects carried away and rejected by the sea, together with a slide of a seaside scene. […] Experience 77 was an opportunity for several artists to acquire experiences during their work in common and submit the fruits of these acquisitions to the attention of others. The outcome of these efforts can constitute an incentive for other artists, particularly younger ones, to set aside their worries and work more freely and openly.[6]

The group reunited after years in september 2019 at Iranshahr Gallery on the occasion of Sasan Nasiri’s exhibition to talk and discuss the projects they have realised decades ago.

Ghazel and her associates took the white drapes off the walls and covered the dead bodies, while another associate forcefully asked the spectators to leave. Puzzled and bemused, the crowd poured out onto the street, lingering there for an explanation, which never came, as Ghazel and her cohorts locked the gallery doors and left. According to a reviewer who was himself “shocked” and bewildered by the experience, the audience, consisting of artists and intellectuals, was angry, sneering, and critical. The performance, like Ghazel’s other works, had evoked a “so what” response. Some felt they had been had and played with (Tahbaz 1999b/1378). Both the form and the content of her work were rather daring and unusual for Iranian audiences. In an interview later, Ghazel responded that many Iranian artists were producing decorative art for the market and that they failed to appreciate ephemeral art with ambiguous or complicated content that could not be sold or hung above the mantle (Tahbaz 1999a/1378). Ghazel’s performances, installations, and happenings in Iran were all “underground,” in the sense that they lacked the official permission generally required for such things. As she told me, “I never did anything with permission there”[7]

New Media Projects hosted “Archives 1993-1999/ Iran” part of Ghazel’s earlier and less shown video works on Feb 15 -17, 2019. These videos are the pioneer works in the Iranian video art scene: a collaboration of Ghazel with Kaveh Golestan at the Golestan Gallery; a video/ performance show at Gallery 13 (with Roxana Shapour); along with a series of installations that took place in Ghazel’s family orchard in the countryside. Rediscovering these lesser known interventions created in the 90s, merely reflected in the books and journals, were displayed with paper-clippings from the same period, a short spring breeze of social freedoms and press.

4. First international award: Despite the fact that Iranian Video artists’ initial experiences were with analog systems, the outset of Video art in Iran can be considered almost synchronous with the popular use of digital video cameras, computers, and visual software. Since Video depends upon the current state of technological development or usage more than almost any other artistic medium, it took some time for the young generation of Iranian artists to become accustomed to this situation and begin to take advantage of the medium. Accordingly, Iranian cinema received its first international awards in the 1960s and Video art in the first decade of the 21st century.[8]

5. Artistic “happenings” in Tehran: Artists taking their practice to the streets; experimental installation; collaborations between architects, performers and video artists — this might be the stuff of every day in New York, Paris, London, Beirut, but in Tehran, it’s radical. Over the past decade, groups of established and upcoming artists have begun taking their art out of the city’s clutch of contemporary galleries and displaying it instead in houses due for demolition, on the back of trucks circulating the expressways, in old military depots, and in half-built high-rises.[9]

The video became a medium which could be posted on CDs and later on uploaded on the web in the mid 2000 as the early ADSL internet arrived in IRAN, and crossed every boundary without hesitation of custom regulations/shipping and insurance costs. Even when the art market boom started to take off and encouraged many to keep producing larger and shinier art objects, some have prefered to remain on the non-material time based media. Video Screening both as an educational format and an exhibition alternative took to New York & Paris and cities across Brazil and academic spheres across North America and Europe. Parking video Library, founded in 2004 in Tehran, was partially involved in many of these moments and later brought examples of Iranian Experimental film and video art to Film Festivals as well in Rotterdam, Gothenburg and Beijing.

For the closing I would like to share a curatorial experience of mine, interestingly I have been practicing some sort of Exhibition-making / online journalism and exhibition design at the early stages of my artistic practice, without having heard the word curating, here I quote two interviews with Vahid Sharifian(published in Tandis biweekly Magazine) weeks happening after the show ended in Spring 2006.

The exhibition was criticized to some degree as it questioned the already shaky aesthetics of those days created/reinforced by the mixture of academia and the conservative elite on one hand and the state cultural policies on the other, but the exhibition almost managed to escape the censorship due to its scale and chaotic spirit.

Here is a small section of a longer interview with Tandis Magazine on the Occasion of Deeper depression:

Vahid Sharifian: What was the basis and purpose on which this exhibition was developed?

Amirali Ghasemi: The whole idea of this exhibition was to create an opportunity for trial and error and experimentation, to challenge the norms without worrying that it might include/display a series of bad or mediocre works on the wall; (You could not see such things in the mainstream exhibitions and biennials those days ). Everyone is entitled to make mistakes. This exhibition is an opportunity for all the participants including me. Everyone is invited based on their readiness to take advantage of this opportunity. To put it more simply, this exhibition intended to shed light on a slice of the potentials and explore capabilities that exist in today’s art community. These capabilities are sometimes overlooked due to some value judgments, personal preferences, tribal attitudes, and of course trends and tastes. Let’s also not forget that the exhibition 2nd title is “contemporary art as a collective experience”. It doesn’t mean that we are keen to hold a “great exhibition”; We just tried to announce that there are such capabilities out there. The most important feature of the exhibition is that there is an interrelation among all selected works. That is, the final meaning is made through the arrangement of distinct works, by various artists, next to each other. These works, on the whole, are the response to the title “Deeper Depression”. You might see contradictory ideas, works devoid of harmony and accord: Because we tried our best that the answer encompasses as many varied responses as possible.

V.S.: all these points regarded, how do you personally evaluate the outcome of making this exhibition for yourself and today’s art scene in Iran?

A.G.: One could see specific works that were not usually on display in the exhibition spaces before. Take for example the poetry performance at “Tarahan-e Azad” Gallery. Usually, the literature community and the performance artists (I don’t mean dramatic literature, of course) are not interconnected to each other. On the other side, the literature is usually not in good terms with typography. Both have their own barriers. Such connections were made possible in this exhibition. Moreover, some audiences and participants, who usually didn’t know each other, became interested in alternative approaches offered by artists from different disciplines. Or there are plenty of capable poets or fiction authors who never get along with an art gallery atmosphere and vice versa. Another example is some photographers who had never encountered poetry before and this exhibition might have encouraged them to do so. In fact, we tried to expand our audience type. In my opinion, this was one of the positive points of the exhibition, since nearly 4500 visitors came to the opening only at Tehran University’s art gallery.

Hope you are doing fine during the pandemic and staying safe, as I mentioned in the beginning, we all have been through a lot. Since I started writing this text in oct 2019 and now finishing it in May 2020, there are serious questions about future, especially our lives and how they are re-defined by our access to the Social Media, News Outlets and Medical care, The fact that we belong to a class which had access to remain “connected” during the lockdown and what did we do with did we consume content and entertain ourselves or did use these often neglected aspect of these technologies to stay sane and help others.

Thanks for the chance to contribute and your patience in receiving the text, it was somehow the longest period of writing in progress which I experienced.

- Motarjemzadeh, Mohammad. “Photography in the Grey Years (1920–40).” History of Photography 37, no. 1 (2013): 117-25. doi:10.1080/03087298.2012.738550 ↑

- Jamal Umid, Tārīkh i Sīnamā yi Īrān: 1279 1357 [The History of Iranian Cinema: 1900 1979] (Tehran: Rawzanah Publications, 1995), 1035. ↑

- Semati, Mehdi. Media, Culture and Society in Iran: Living with Globalization and the Islamic State. Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, 2010. ↑

- Cafferty, Erin Mc. 2012. “Kamran Dibat.” Contemporary Practices: Visual Arts from the Middle East, no. 11 (July): 126–28. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&site=eds-live&db=asu&AN=84432344. ↑

- Farid Jahangir and Sassan Nassiri, Bita Fayyazi, Ata Hasheminejad, and Khosrow Hassanzedeh.” The Cube Project Space. http://thecubespace.com/en/living-as-form/farid-jahangir-and-sassan-nassiri-bita-fayyazi-ata-hasheminejad-and-khosrow-hassanzedeh/. ↑

- Etemadi, Shahla, Experience 77, Tavoos Iranian Art Quarterly, No. 1, Tehran 1999 ↑

- Naficy, H. (2011): A Social History of Iranian Cinema, Volume 4: The Globalizing Era, 1984‐2010: Duke University Press (A Social History of Iranian Cinema ↑

- Habib, Susan. “Video Art as a Rising Medium in Iranian Contemporary Art.” Academia.edu. https://www.academia.edu/734261/Video_Art_as_a_Rising_Medium_in_Iranian_Contemporary_Art?source=swp_share ↑

- Carver, Antonia. “Dead Dogs.” Bidoun. July 01, 2004. https://bidoun.org/articles/dead-dogs ↑